Man, where to start. How about with John Mellencamp:

When I was five I walked the fence while grandpa held my hand

“Rain on the Scarecrow” came out in 1985, the year Growing Up Dead in Texas happens. Or, that’s when the events happen. Right around that time I remember walking the fence with my great-granddad, Pop. A hot fence, to keep the cattle out of the ten acres my grandma’s house was (and is) on. And I knew it was hot by then, of course; I’d been zapped a few times, sneaking out there to chase whatever animals I could scare up. But still, Pop, he held his hand out to me, a particularly evil glimmer in his eyes, a smile ghosting the corners of his mouth up — he had to have been at least eighty, then — and I took his hand, and he smiled, clamped his other hand onto the fence, shooting that jolt across to me. And then we did it again and again, because it was so fun.

I think in everything I do, that jolt, it’s what I’m looking for. From old phone generators to neon hotel signs, I’ve shocked myself in so many ways. I remember pulling a fertilizer rig back and forth across an irrigated field one day — which is about the most boring thing you can do — when I started to nod off, but then figured out how to stay awake: I could stop the tractor, climb down, and pop a sparkplug wire off, stick my finger in. It would just about knock me down, but I did it over and over that whole day. To stay awake, I kept telling myself, laughing and crying out there in the dirt and the poisoned owls, a two-liter of warm Cherry RC waiting up in the cab for me. Except I think I already was mostly awake. I just wanted to go back, really.

I think in everything I do, that jolt, it’s what I’m looking for. From old phone generators to neon hotel signs, I’ve shocked myself in so many ways. I remember pulling a fertilizer rig back and forth across an irrigated field one day — which is about the most boring thing you can do — when I started to nod off, but then figured out how to stay awake: I could stop the tractor, climb down, and pop a sparkplug wire off, stick my finger in. It would just about knock me down, but I did it over and over that whole day. To stay awake, I kept telling myself, laughing and crying out there in the dirt and the poisoned owls, a two-liter of warm Cherry RC waiting up in the cab for me. Except I think I already was mostly awake. I just wanted to go back, really.

Growing Up Dead in Texas is about that.

But then there’s Joan Didion, too:

Writers are always selling someone out.

She’s not wrong, I don’t think. All the books and stories before, I’ve always pretended I wasn’t in them. Because if I’m not, then that makes everybody in the book also not people I actually know, right? It makes them not my family, not the people I grew up with, and because of, and in spite of.

Growing Up Dead in Texas kind of collapses that. About two books before it, I wrote this other novel, a horror story — not published yet, if ever — just to see how far I could go. How far I shouldn’t go. It made me sick, writing it; I lost a lot of pounds those six weeks. But then I surfaced a better writer, I thought. Not because I’d got the horror washed out of my head (that never seems to happen), but because I knew now I could go places I shouldn’t go. Growing Up Dead in Texas is the next step in that progression, for me. In it, I went to the one place I thought I had no place being anymore: home.

Growing Up Dead in Texas kind of collapses that. About two books before it, I wrote this other novel, a horror story — not published yet, if ever — just to see how far I could go. How far I shouldn’t go. It made me sick, writing it; I lost a lot of pounds those six weeks. But then I surfaced a better writer, I thought. Not because I’d got the horror washed out of my head (that never seems to happen), but because I knew now I could go places I shouldn’t go. Growing Up Dead in Texas is the next step in that progression, for me. In it, I went to the one place I thought I had no place being anymore: home.

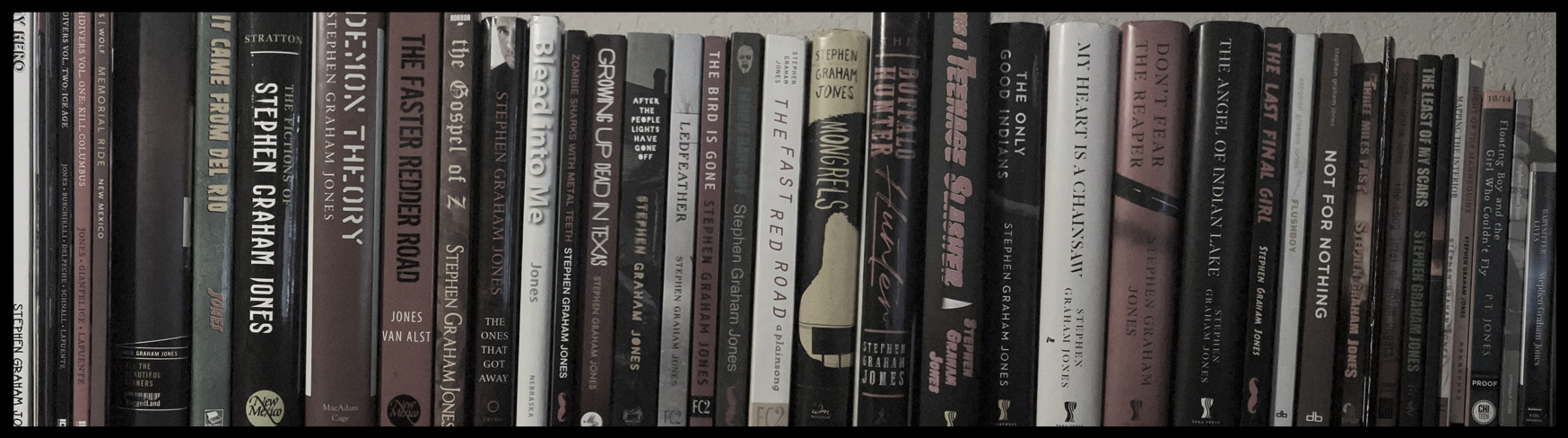

That isn’t to say I hadn’t been dancing in its general area, though. My first novel was set in Clovis, New Mexico, which was close to West Texas. I’d set another novel up in Nazareth, Texas, which is a lot like home. I’d written one that was set down around Del Rio, kind of tending towards Austin, and the novel I wrote immediately before Growing Up Dead in Texas, it happens in Lubbock, Texas, just a hundred miles away, and one that just came out last year, it’s set over in El Paso. Another, coming out in 2013 but written before 2008, it’s secretly taking place in Dallas, and one that’s out in 2014 (also pre-2008), it’s set right in Stanton, which is just five minutes from my grandma’s. From Greenwood, Texas. So I feel like I was definitely circling West Texas, anyway. But it was getting obvious that I was avoiding it. To me at least.

I just needed a trigger. I just needed permission.

That came in 2008, when I hired on here at CU Boulder. When they were interviewing me, one question they asked was How would leaving Texas impact my writing? It was the right question. My stab at an answer was that Leslie Marmon Silko had to go to Alaska to finish Ceremony. That James Welch did a lot of his Winter in the Blood work in Greece. That, in order to properly mythologize a place, you need distance. And, for me anyway, it had always been that way; my characters have always been at least four years younger than me. Just because, until I was thirty-six, I had no clue what it had really been like, being thirty-two. I needed some time to think about it. I needed that distance.

That came in 2008, when I hired on here at CU Boulder. When they were interviewing me, one question they asked was How would leaving Texas impact my writing? It was the right question. My stab at an answer was that Leslie Marmon Silko had to go to Alaska to finish Ceremony. That James Welch did a lot of his Winter in the Blood work in Greece. That, in order to properly mythologize a place, you need distance. And, for me anyway, it had always been that way; my characters have always been at least four years younger than me. Just because, until I was thirty-six, I had no clue what it had really been like, being thirty-two. I needed some time to think about it. I needed that distance.

So, yeah, like the very first line of Growing Up Dead in Texas says: I moved. I left Texas. I even sold my favorite truck, so I wouldn’t be reminded all the time. I’d left before once for a couple of years, for my PhD, but had come scampering back the first chance I got. Just because it’s scary, leaving your home, the main and only place you know. Or want to know. It almost feels like you’re going to lose your identity if you can’t see it all around you, if you can’t always be confirming it. But. If you can get it down on the page the right way, some lucky way, then, yeah, you can leave once and for all.

At least I have.

But still. You know how Tim O’Brien talks about story truth and happening truth in The Things They Carried, and how story truth is actually what matters? I believe in that, completely. That a lie isn’t a lie if it’s peeling back the skin of something that feels real. Something that is real. I believe Richard Hugo in Triggering Town, when he says that, when you’re writing about your hometown, if for some reason you actually need the water tower to be on Rose Street instead of St. Francis — you need the shadow to fall here, you want somebody to be able to read the graffiti from there — then, yes, by all means, move it, who cares, it’s the story that matters, not the facts.

Check how Orson Scott Card starts his “Lost Boys” story:

I’ve worried for a long time whether to tell this story as fiction or fact. Telling it with made-up names would make it easier for some people to take. Easier for me, too.

The nightmare I keep having with Growing Up Dead in Texas, it’s that I’ve forgot to change somebody’s name. Or that I haven’t changed it enough. Or that I’ve used it somewhere they wouldn’t have wanted it used. I dug up all my old yearbooks — for some reason I have most of them, but hardly any pictures, no home movies — but, honestly, paging through them now, knowing Growing Up Dead in Texas is coming out, it’s terrifying, it keeps making me think that there’s no going back anymore, that I haven’t done the place justice, that I’ve sold it, even.

Which isn’t at all to say I can ever leave, either.

What I tell people all the time is that, really, we can only ever accurately render an emotional landscape we’re uncomfortably intimate with. And the contours of my life, they’re all West Texas, Permian Basin, Midland County. Greenwood, Stanton, over to Big Springs, up to Lamesa. I’ve left blood on every last part of that land, and that’s where most of my people are buried. So, no matter if I’ve set my story on Mars or in some made-up past, still, I’ll always be writing what I know, I’ll always be writing the only place I know. I’ll always be sending me and my best friend out into the mesquite scrub for the day, to make up a world worth living in.

Here’s how Neil Gaiman’s narrator opens up “Feeders and Eaters”:

This is a true story, pretty much. As far as that goes, and whatever good it does anybody.

That ‘pretty much,’ that’s where Growing Up Dead in Texas lives and breathes. A month or two ago, I was reading an article about the post-modern memoir, I think it was. Which, I’d never thought about the memoir for longer than about five seconds in a row, so, tagging ‘post-modern’ in front of it just made me realize that I’m completely out of the loop, here. So, that article was particularly instructive. Kind of as an aside, it differentiated the biography and the memoir for me: where biography is kind of like a bullet-point list, or an annotated time line that corresponds to and entails all the real and verifiable ‘facts,’ memoir has more to do with what those facts felt like. The memoir is about looking back to what- and whenever, and trying to extract or impart some meaning, first for the narrator, second for the reader. But it’s the writer’s wrestling match with meaning that makes the dynamic work, that gives shape to the narrative.

Is that close? Does everybody know this but me?

Probably. Non-fiction’s never been able to hold my interest for very long. Ursula LeGuin says it better than I ever could, of course:

we have come to place inordinate value on fiction that pretends to be, or looks awfully like, fact

Which I have some fundamental block, trying to understand. Not LeGuin, but the impulse she’s indicting, how ‘based on a true story’ can sell something, when what should matter is  whether the story moves you or not. Still, in hopes of understanding, I read Devil in the White City, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, all that A-list kind of stuff, just to pretend I was connected — completely dug them, too — but, when wandering away from the fiction shelves, I tend to end more at Oliver Sacks or Redmond O’Hanlon, I guess. Or the paranormal shelves, all the disappearing hitchhikers and earnest testimonials about monsters by the lake.

whether the story moves you or not. Still, in hopes of understanding, I read Devil in the White City, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, all that A-list kind of stuff, just to pretend I was connected — completely dug them, too — but, when wandering away from the fiction shelves, I tend to end more at Oliver Sacks or Redmond O’Hanlon, I guess. Or the paranormal shelves, all the disappearing hitchhikers and earnest testimonials about monsters by the lake.

That Joan Didion quote I opened with? I have no clue what it’s from. I’ve never read even one word she’s written. Which, I’m sure I should have, yes; Caitlin Flanagan’s write-up more than convinced me (it also convinced me I need to read Flanagan). But, man, non-fiction, my conception of it’s always been that it’s too hemmed in by facts. Which is stupid, I know. Dennis Covington’s Salvation on Sand Mountain, it’s flat-out amazing, might have changed me in some fundamental way, and, as far as I know, there are no lies between its covers. But, before writing Growing Up Dead in Texas, I’d only ever read one memoir, and that’s one that I happened to blurb: David Goodwillie’s It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time. And it rocked; it completely drew me in, did with me what it wanted, which is exactly what a story should do. Still and all, though, what hooks me into a story, it’s never ‘written by this person’ or ‘documenting this event or time period,’ it’s always . . . I don’t know. No, I do know: it’s whether or not there’s werewolves on the cover, really. Or at least the promise of werewolves. Premises and situations sell me. Not people.

Nevertheless, here I am, with a book that’s very memoiry, if it’s not quite a memoir. And, to write it, or, once I realized what I was writing, I had all these grand plans to immerse myself in non-fiction, to learn the form, the devices, the tricks, the pitfalls, the pratfalls. And I tried. I really did.

I got a few books, mostly recommendations, some off the good-selling lists, some just because they had a cool title. And I kept reading a page or two and ending up just staring at the wall instead, or playing games with counting my fingers over and over, faster and faster. History so doesn’t interest me, even true-crime always leaves me wanting, and I finally figured out that what always kicks me out of a non-fiction read, it’s that I know the narrator’s reliable, or that I’m supposed to be reading the narrator as reliable, anyway. Which is maybe why Beautiful Boy kind of worked for me: I don’t read it as fact, I read it as a sophisticated, emotionally-resonant defense, a rationalization, and you can never trust narrators who are playing that game. Which is specifically what makes the game worthwhile, for me. I mean, I feel like I kind of cut my writerly teeth on John Barth,  Thomas Pynchon, Philip K. Dick, and everybody in or from that particular rabbit hole (Calvino, Eco, Coover, on and on, wonderfully). Which is to say that shifty sand, that indeterminacy, those games, I had and still have a serious taste for them, so long as the story has an authentic emotional core (case in point: The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor). And the memoir, outside of Frey and Nasdijj and that crowd, it doesn’t quite satisfy in that regard. Or, it has to catch me unawares, anyway (see Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water for one that’ll catch you off-guard).

Thomas Pynchon, Philip K. Dick, and everybody in or from that particular rabbit hole (Calvino, Eco, Coover, on and on, wonderfully). Which is to say that shifty sand, that indeterminacy, those games, I had and still have a serious taste for them, so long as the story has an authentic emotional core (case in point: The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor). And the memoir, outside of Frey and Nasdijj and that crowd, it doesn’t quite satisfy in that regard. Or, it has to catch me unawares, anyway (see Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water for one that’ll catch you off-guard).

So, my good intentions to be responsible and know the genre of non-fiction, they fell apart immediately. I did find salvation, though: MonsterQuest. That was my model for Growing Up Dead in Texas. I recorded every episode that came on, and watched and watched and watched again, trying to nail down the formula, how to balance dramatization with interview, where to interject facts. And it was so, so instructive. I felt like I understood non-fiction, like I had an idea about what the audience would and wouldn’t tolerate. I felt like I had an inkling what they were expecting, too. How they liked their material delivered. And it wasn’t about the facts at all, it was about the shape of the writing. The form.

Where fiction has to at least acknowledge a plot, non-fiction instead has to continually circle an issue, an event, a question. Like, it almost has a thesis statement, and then all these other pieces that serve as support, or contributing investigations. But I never saw it  that linear, that five-paragraphy. For me it was always a solar system, one wildly out of control, spinning fast to its doom, all the planets breaking orbit, diving headlong at the sun, trying to be first to die, or the brightest, anyway. And that impulse, that jolt of diving into the sun, that was something I could connect with. That I was already connected with.

that linear, that five-paragraphy. For me it was always a solar system, one wildly out of control, spinning fast to its doom, all the planets breaking orbit, diving headlong at the sun, trying to be first to die, or the brightest, anyway. And that impulse, that jolt of diving into the sun, that was something I could connect with. That I was already connected with.

So, thank you, MonsterQuest. I’d have been lost without you. In more ways than one.

As for the more literal Why I wrote this (for why I write, try this, or the not-in-the-book dedication for Growing Up Dead in Texas), that’s a lot simpler. My grad fiction workshop my first year at CU, I of course told the students they had to write a novel over the next fifteen weeks. In addition to the four or five stories they’d need to be submitting. And there was the usual resistance, sure. But one of those students, in kind of complaining about the stupidity of this kind of effort — I agree: you don’t write novels because it’s the smart thing to do — said What about you, prof?

Again, it was the right question.

I said Sure, if they wanted, I’d write a novel right alongside them, just to show that this was a possible thing I was proposing forcing them into. So, that next week, I remembered that I’d said that, and, wrote the opening to Growing Up Dead in Texas:

At that point in the novel, I was a hundred percent committed to telling no lies. To only writing things that were true. Until then, I’d only ever tried that particular trick once (lie*), and it lasted just about two pages as well. The impulse to lie is strong in this one, yes. However, with that kind of preface, taking things from my real and actual life, where could I go, right?

Everywhere, as it turned out. It’s surely no coincidence that this book is coming out in 2012, when I’m forty, while the narrator for Growing Up Dead in Texas, he’s sitting about four years younger than that, by my math. Which, it’s easy math, yeah; him and me were kind of born the same year, the same town, the same room, even.

And I need to go back to that grad fiction workshop one more time: a student in there, she asked Since we were doing this stupid thing of writing a novel in fifteen weeks, how exactly is a thing like that done? And, though I’d been teaching a while, and had had many more workshops write novels by then, I’d never been asked specifically that. It’s such a big question. The obvious answer is “You just write it.” But I’m supposed to be better than that. So I kind of heard myself answering, documenting how I’d written my first novel. Which, all I did that time was, every time I hit a wall, I’d just mine my own life, pull something out of my head Howling-style and plop it onto the page, make it work.

Meaning, after the preface above, I figured I’d better make my answer true, since I’d said it like it was true. And, since the first wall I hit was the first page, I started mining immediately, and kind of heedlessly. And, no, I’m far from the first novelist to think it would maybe be cool to have a narrator who sometimes has my name. Exactly two weeks after finishing Growing Up Dead in Texas, I read Brett Easton Ellis’ Lunar Park (by far the scariest book I’ve ever read, at least if I don’t count The Girl Next Door), which does the same thing, and then there’s Raoul Duke, Kilgore Trout, and for a while wasn’t David Lynch kind of using Kyle McLaughlin that way too? As for exactly where I got that trick, though, it’s the same place I got the narrative hand-off fun happening in Ledfeather: Philip K. Dick. That time, the book was Radio-Free Albemuth; for Growing Up Dead in Texas, my model was more VALIS — the second draft of Radio-Free Albemuth, pretty much.

However, the photo on the front of VALIS, it’s not PKD as a kid, is it?

That’s me and my brother. And what I wouldn’t give to know what book that is I was trucking through the pecan trees that day. Or even to know for sure where I was, then. Where we were. I think it was this pecan orchard we lived in when I was twelve. This little half-length-but-double-wide trailer that’s far and away the best place ever (it snowed that year). But that looks so much like my grandparents’ house behind us, too. Except for the shed. And that they didn’t have that many pecan trees. But, for those of you who don’t know West Texas: that’s it, pretty much. Flat as you can imagine, if not flatter. Shades of brown. A sky that goes forever.

I’ll never go back, but I’ll always love it, I think.

And, finally, that’s why I wrote Growing Up Dead in Texas. I mean, I can dress it up as a challenge, or pretend it was me being sick of non-fiction eclipsing novels, or even pretend it was all some happy accident.** But really, I think it’s that I miss that place. And that person I was then. And I fully believe that, like Billy Connolly says:

If I tell it right, you will hope it’s true.

If I can do that — have any of you seen that “Inner Light” episode of Star Trek: the Next Generation? In it, the crew of the Enterprise, they encounter this strange probe, which mind-hijacks the captain into some kind of ‘past document.’ Into a dramatic recreation of what this now-gone culture was like. The nuances, the people, the grit of the place; the magic. And then, after letting him live a whole life in that, as somebody else, as one of them, it spits him back onto the deck. Only, he’s different now. He’s been somewhere. The story of these people, it’s taken him to a place he knows is real, to a place that can now never be not-real for him.

If Growing Up Dead in Texas does even half of that, even a quarter, then that’s all I ask.

*

I have a short piece in Llano Estacado: An Island in the Sky called “What I Remember” (I think I sent it in without a title, so they put that one on there), which is kind of like all of Growing Up Dead in Texas distilled into four pages, and minus all the people. Except Pop.[ go back to where you were ]

** talking happy accidents: Growing Up Dead in Texas likely never would have happened without Craig Clevenger. He was in a bar in San Francisco — might have been this certain bar/art gallery that’s not there anymore — reading a spiral-bound copy of it I’d mailed him, and a couple of people interning at MacAdam/Cage were there as well, and got to reading over his shoulder, and then got to absconding with the manuscript. I gave them their own when I was in San Francisco next, but the Cage wasn’t buying manuscripts at the time, I don’t think, and I wasn’t submitting anyway. However, one of the people working for them, Guy Intoci, he hired out to MP Publishing a couple of years later, as editor-in-chief, and he’d read Growing Up Dead in Texas while it was in the office, and called me up about it, and my agent and me hadn’t even ever got around to submitting it anywhere else, and this too is one way a book can happen, if you’re lucky. [ go back to where you were ]

should have had this up in there in the pullquotes. from Michael Martone, via Matt Bell: “If I am a fiction writer, I am going to create fictions that do not in any way say they are fiction. Fiction as fiction. Fiction as totally camouflaged fact.”

Great post — on writing, on the idea of truth and lies and story. I look forward to picking the book up. I love West Texas, so seeing those pictures reminded me of various places there.

should have put there, but I’m only just now finding it. in METAMAUS: “in journalism it makes a difference if a fire happened, in a novel it’s just how well one can describe a fire.”

this too, via Neil Gaiman (Sandman 17) : “This is magnificent — and it is true! It never happened, yet it is still true. What magic art is this?” Then again, later: “Things need not have happened to be true.”

via Joe R. Lansdale (Freezer Burn, p.212) : “I never said it was true. I said it was a story I got.”

via Lindsay Hunter: “None of this is true, of course. It’s just the easiest way to explain.”

one more, from Neil Gaiman, talking about Ocean at the End of the Lane: “it’s not actually autobiographical but that kid was me.” (interview: http://www.bigissue.com/features/letter-to-my-younger-self/7316/neil-gaiman-interview-stephen-king-gave-me-the-best-piece-of)

from the end credits of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/81dc3a29ae577cc854800eccfc323e8a2f909047acdedfb22cdd3cab022c2030.jpg