Back in the late nineties, I’d see Stephen Dixon stories all over and flip back to his author bio at the end of the journal or whatever not because I didn’t already know it, but for the rush: it always said he had some three hundred stories published. I had maybe six at the time? Three hundred was an amazing, impossible, never-get-there kind of number. And I’m not there yet. This isn’t that post. Though I did just total up my stories from print- and e-mags and anthologies and best-of-the-years and textbooks, meaning there’s some doubling, even some tripling, and maybe a ‘forthcoming’ or three sneaked in (I did manage not to count novel chapters that ran in different places, anyway), but still, sitting at 201, looks like. Since my first publication in Black Warrior Review back in 1996 (well, ‘first’ would be this little mag MindPurge, then there was North Texas Review. But BWR was the first I got a check for. And checks matter). Still chasing Dixon, though.

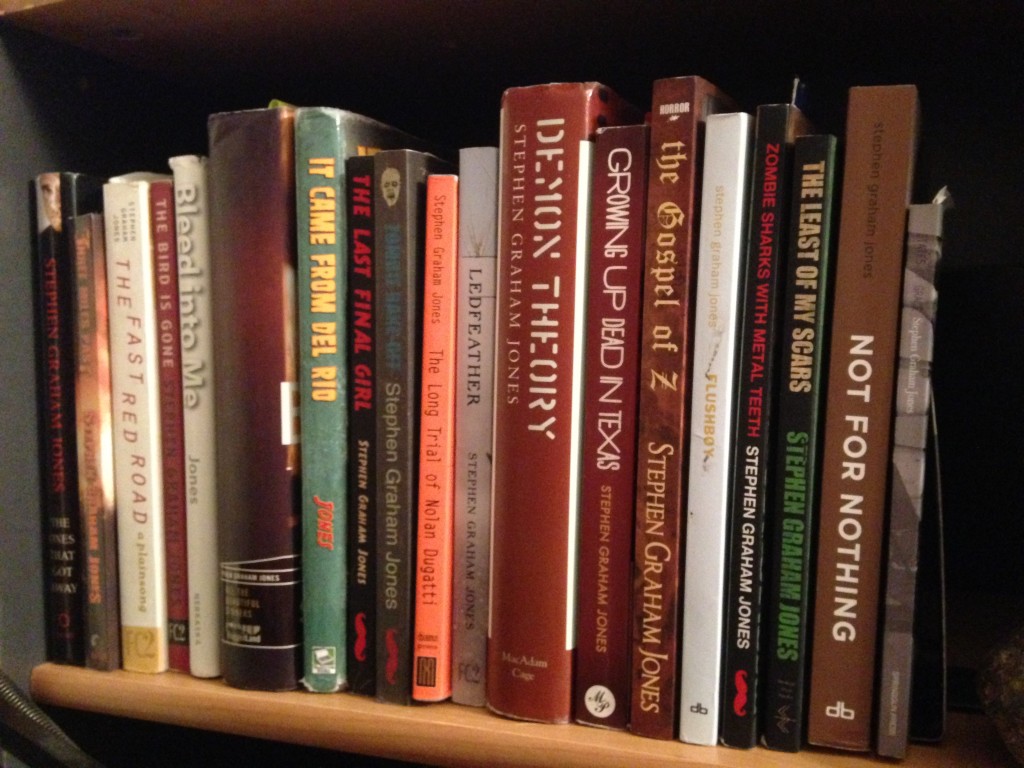

And, as anybody who’s ever requested a bio from me knows, that’s the thing I suck at the most. I’d far rather just write another story. Or make up a bio. Just because I can’t keep track. But, near as I can tell, here’s the count as of early March, 2014: fifteen novels (just counting ATBS once, though it’s now two way-separate novels, and including Not for Nothing, already on some shelves), five collections, one e-novella that’s soon to be print, and another novella going print and e- right about the same time (this month—an early review). And this total includes Seven Spanish Angels, which is e-only, in a “rEprint” series though it’s not really a reprint (it’s complicated).

These numbers change fast, though: I have a co-written YA (Floating Boy and the Girl Who Couldn’t Fly, with Paul Tremblay) out in April, in Canada / October in America, and also in October, another horror collection (After the People Lights Have Gone Off, from Dark House), and it’s looking like Once Upon a Time in Texas might just be out right around the same time. That’s the second installment in The Bunnyhead Chronicles, for any Bunnyhead fans. Also, I just a couple of days ago figured out the shape of the third of that trilogy.

There’s stuff waiting in the wings, too. Think right now I have three novels primed and ready to go. Two horror (one slasher, one werewolf, each the single best thing I’ve ever written or probably ever will write), and one very much in keeping with Growing Up Dead in Texas, except less generational and a lot more bow-hunty, and featuring the by-far best ending I’ve ever lucked onto, bar none, except one way-broken novel that’ll never see publication. And I’ve got one (horror) I need to re-hab into that rarest of all beasts: an actually working novel.

And, #WritingNow? A screenplay. It’s a slasher, of course. Slasher’s the truest of all genres, I think. It’s where I’m most at home, anyway. Where I feel I can be the most honest. Though more and more, lately, there’s this haunted house / visitation kind of novel making it hard for me to cross dark rooms. Hard to even turn the lights off. Hard for me to deal with open doors behind me. Feels like a big novel, too. ‘Big’ as in ‘many pages.’ Though I wouldn’t doubt if I wrap myself up in some novelization / tie-in kind of stuff before too long, here. I think there’s things to be learned in those fields. I dig the learning. When I can get paid for it: even better. However, don’t be surprised if 2015 for me is more or less bookless. Been talking to some people who know, and it may be the case that I’ve been publishing too much, as unintuitive and not-the-dream as that sounds. I could have a book out every other month, I mean, with no problem. Trick is, making them stick, right? That’s what I’m still learning.

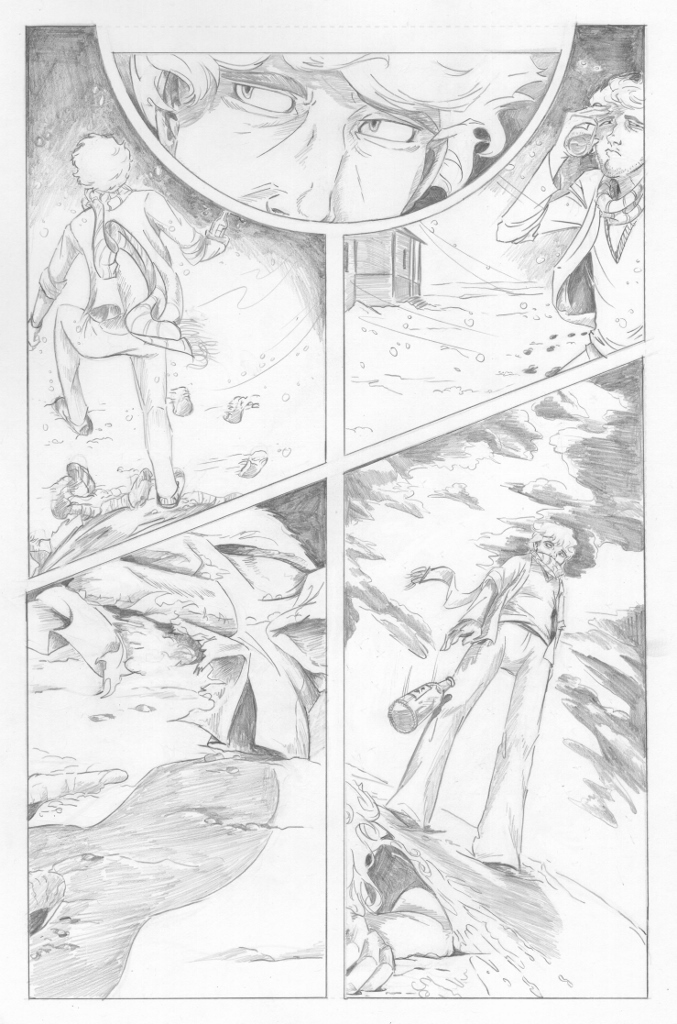

And, talking updates, there’s A Critical Companion to the Fictions of Stephen Graham Jones out from UNM Press in 2015, edited by Billy Stratton. And, not in that novel-total up there because it’s a book, not a novel, there’s the blindness overtaking me is beating like a drum, an extended conversation/interview me and Pablo D’Stair did in 2011 (me and BEE have real blurbs on a fake book in Pablo’s recent movie). And there’s another book related to that that I can’t talk about yet, as jinxes are real. But hopefully soon. And, that first issue of Demon Theory with Delicia Williams is still in pencils. Hopefully to someday be real; I’ve got the rest of the scripts for “Demon Theory 16” down, too. I so dig working inside the comic book page, and, in writing the script, have discovered things about that first act of Demon Theory that I hadn’t seen before.

And, now that I’ve got some twenty books on the shelf? What have I learned? I’ve had friends win a lifetime of money with a book contract, and I’ve had friends win the Pulitzer. I’ve seen friends write perfect bulletproof immortal impossible gems of novels, only to have nobody notice, and I’ve seen other writers I know and dig kind of drift away, into other ventures. Not because they weren’t talented or because they got burned one too many times, but because fascinations change, I think. Talents redirect. Life pulls, and you follow.

And, over the past fifteen years I’ve connected with a lot of readers, which is wonderful each time. That title story for Bleed Into Me, I’ve had so many people tell me that that’s what it’s like. And Ledfeather‘s gone all over, and taken me with it, and Demon Theory has opened so many doors, and the rest of the books have booked me on flights and gotten me GoH seats in just about all the contiguous states of America, I think (except Nevada and Arizona, for some reason). But, what have I learned?

This feels suspiciously like there’s a colon on the way:

- Sometimes editors are right. I mean, even a lot of the time they’re right. And this isn’t about me once having had ‘principles’ and now, for money, compromising. The clickover point, it wasn’t one single editor magically fixing a manuscript, either. It was that movie Ravenous. One of the times I watched it, I checked out the deleted scenes, with the commentary, and there was (director) Antonia Bird talking about how the producers cut this, cut that, and there was something a touch mournful to her tone, but I agreed with those cuts, too. I saw that this wasn’t producers swooping in, trying to leave their stamp on the movie just for ego’s sake. This was somebody trying to make the movie sell. They were packaging it to be a better product. Which is of course what’s first, last, and in the middle of any good editor’s suggestions, I have to hope. Literary integrity’s great, but even more important is getting somebody to pluck that book off the shelf in the first place.

- Poor timing and bad luck are real. Which isn’t news to anybody. So often ‘your’ idea or manner of execution gets to the shelf just about the time you’re delivering your world-changing manuscript to your agent. At which point your great idea is suddenly derivative. There’s nothing to do about this. Just be happy that it was, in fact, a salable idea. And then have another idea, and write it faster this time. Sitting around moaning about the injustice of that King upstart writing your telekinetic high school outcast novel doesn’t accomplish anything. Just, now, start your big haunted hotel novel . . .

- Write the same way you read. Which is to say: in the line at the bank, standing there pumping gas, on the bus, wherever. When a book you’re reading is going well, you sneak a few pages in whenever you can, don’t you? Write that same way. It’s what I’ve had to learn to do, what with all the other busy-ness of life always trying (without any malice) to steal all my writing time. Steal it back. Easy as that. This isn’t to say that schedules and discipline are bad, either. I’ve just never had any time for them. Any need for them. When I’m writing, then the whole day or week or month is for writing. Everything else has to somehow schedule itself in.

- Don’t write novels you know you can write. Every time you open a new file, you should be fairly certain that the magic isn’t going to be there this time. The project’s too unwieldy, the concept flawed, you don’t have this or that figured out—you don’t know where or how to even start. Start anyway. Writing novels you know you can write would be so unfulfilling, I would think (though, there’s ‘fulfillment’ and there’s the electricity bill, yes). I want to feel like I caught something new, not like I caught the same butterfly as last time, and the time before. However, of course the market wants that same butterfly, doesn’t it? Don’t let the market tell you where to drag your net, though. Go out and find something nobody knew existed. And then put your name on it. And then go out again, into even wilder territory. Or into the darkest subway in the biggest city, where nobody’s even seen a butterfly for a generation. It might be there, though. You’ll never know if you’re not there too.

- Humor doesn’t mean your work isn’t serious. There’s nothing wrong with jokes, with slapstick, with bits and rants, even. Coming up through grad school, it seemed none of the stuff we read had any smiles in it. It was all serious and dour and subtle, which I took to be code for ‘literary.’ Having fun on the page, though, man, isn’t that what it’s all about? Do we not love those books which made us laugh out loud, then cry and cringe as well? Stories need to run the full gamut of this human experience. Don’t be afraid to try.

- Don’t write for the ages. And don’t write for the critics. Write what you want to read, instead. Act like you’re paying back into a system that’s been investing in you since you could read. Write like you owe it to fiction. Write because you’re sick of what you’re seeing in the world, on the shelves, or write because you’re all starry-eyed with love. Just don’t write to try be timeless, to put your stamp on the world. I’m fairly certain that Shakespeare, for all the good he left, was just jacking around, trying to make a buck, trying to get by until next week. And because he didn’t feel like the whole future was watching, he was free to play, to invent, to explore, to make mistakes.

- Sometimes you get lucky. With a story, with a phrase, with a character, with a whole novel. Every once and again, a novel I’ve just written, it’ll just be there, already what it is,

for better or for worse. And that’ll be the first time out, the first time through. The trick, then, it’s to leave it alone. So many novels get drafted on endlessly, until the heart’s written out of them. At the same time, I once wrote two-thousand pages just to get three-hundred and fifty. Each novel’s different. So of course you shouldn’t try to force each through the exact same process. I’m guessing people who cook use different spoons and bowls and mixers for different cakes. Do that with your fiction as well.

for better or for worse. And that’ll be the first time out, the first time through. The trick, then, it’s to leave it alone. So many novels get drafted on endlessly, until the heart’s written out of them. At the same time, I once wrote two-thousand pages just to get three-hundred and fifty. Each novel’s different. So of course you shouldn’t try to force each through the exact same process. I’m guessing people who cook use different spoons and bowls and mixers for different cakes. Do that with your fiction as well.

- Know when to let go of a story, of a novel. Which is tricky. You’ve got months, say, invested in this, and scrapping that file, consigning it to the drawer, it feels like giving up, like a betrayal. But it’s not. It’s allowing you now to write something without all those mistakes. And I’ve done this. I don’t see everything I start through. Some novels shoot themselves in the foot a hundred and twenty pages in (that’s the magic number for mine, anyway). In the last three years, I’ve got two like that, novels I’m so completely smitten with, yet can tell are already broken. Walk away, man. And don’t look back when it explodes. That’s how you’ll know you’re cool.

- Endings are forever tricky. But when you finally luck onto the right one, you can feel it. Very very rarely will I write a novel and jam the ending first try out. The way it usually works is I slap a temp-ending on at four in the morning, then come back to it before lunch, try another ending out, and then another, and another, until, usually about three days later while I’m playing basketball or trying to track down a plug-wire that’s shorting, it’ll come to me, how it should be. And that release—there’s no other word, is there?—that’s specifically why I write. Not for all the two-hundred ninety-nine pages of craftwork and heavy lifting that came before, and all the regret already built into that, of time not spent with your family or seeing a whale or whatever. I write for that very last page. For that flush, that rush. There’s nothing better.

- Writer’s block isn’t that real. Or, every time I hit that wall of What comes next, instead of indulging in that lack of forward motion and wallowing around in public drama about it, what I do is back up about forty pages, and read so, so closely. The problem’s nearly always somewhere between there and the wall. The wall is just your own storytelling instincts warning you that you made a mis-step x pages back, and if you don’t fix it soon, then this novel’s getting lost, kid. Fix it now or fix it never. I’ve not once been unable to find the so-obvious problem that was keeping me from moving forward.

- Do fiction for money. To condition yourself to get paid, sure, as Harlan Ellison says, but I’m talking more about what Joe Lansdale says: some stories he’s written because they were bleeding up through his fingertips, and some he wrote the same way you build a chair. Sign on for as many of those chair-stories as you can. Every invitation I get for one, I take it. And not just for the money, but to remind myself that I’m a writer, that you can call me at ten at night, ask for a story in this genre of that length, and I can get it back to you in a day or two, and make it not just good enough, but hopefully the best of them all. Art’s a contest, after all: do it better or go home.

- Copyeditors are the bane of my existence. But they save my life on a daily basis, too. I’m a lot stupider than it might appear on the page. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m not about to spell ‘okay’ with two letters, or ‘grey’ with that American ‘A,’ and if any of my characters say to get them a coke, then they don’t mean a Coca-Cola, they mean a Dr. Pepper or a Pepsi—maybe a Coke, sure. But, yes, you’ll have noticed some of my ‘dumpsters’ are now capitalized, as are my bandaids and frisbees and kleenexes. So it goes. You don’t win all the battles. What you might not have noticed is that, say, state lines are in the right place, or generations of families stack up the right way, or a character’s name is actually spelled consistently. This isn’t because of me. I wish I could take credit. Or, I do get the credit. But it’s really the copyeditors. They’re angels and demons both, in a single red pen.

- Have people you trust read your work. And read theirs back. You’ll get good help, and you’ll learn about your own writing—about fiction in general—by giving good help. Sounds very beatific, I know, but your MFA program, the loan might last forever, but the classes won’t. You’ve got to recreate the workshop on your own, from scratch, by trial and error.

- Be able to logline your novel. It’s a screenplay test—is there actually conflict? do you know the story?—but, man, it works so well for novels as well. Which I recently found out at a party: somebody asked what was I working on, and I had this five-minute out of body experience of watching myself stumble through a muddle of half-formed, disconnected scenes, and the person listening doing their polite-eyes thing, and eyeing the level of their drink. So I promptly quit writing that novel, and very quickly wrote another one, that actually worked, that’s got a logline. And always write a version of the back-cover copy, blast it off to your editor or whoever. They won’t use it, of course—you’re a novelist, and don’t know about marketing—but maybe some of its character will make it through. Or maybe a phrase will inspire someone to write the real killer copy. Either way, it tells you what your novel is, what it’s about.

- How long it takes doesn’t matter. The last novel I wrote took sixteen days. And the one before that, fifteen days. One before that, thirteen. That doesn’t mean they’re necessarily ‘slight’ or inconsequential, though. That’s just the way I write. And some people, they do their best work across a couple of years or more, cobbling the novel together a bit at a time. It doesn’t matter either way. What matters is the product. Used to, when I’d kick a novel out in four weeks, I’d feel halfway guilty, like I didn’t understand the toil, the struggle, the heartache. But each of those novels, they left me in tears, writing them. And not just because I’m a wimp. I mean, I am, but I don’t think that factors in, really. You know when you’re writing real. And that’s got nothing to do with the calendar or the clock.

- Stay off of Goodreads. And don’t respond to comments on Amazon or wherever, either. I mean, we all go there half-squinting, trying to just read the good reviews. But you always think the good ones are by one of your mother’s many on-line personas, while the bad ones, they’re from the Mount, man. They’re gospel, they’re true, and, worse, they’re formative. The main feedback you need? Your royalty check. That’ll tell you whether you’re doing it right or doing it wrong. Which isn’t to say I’m not so thankful for all those comments and Goodreads reviews. I am, extremely, even the one-star jobs; people are engaging the work. What more can I ask for? But my mind and ego are way too fragile to open my heart and rub it all over the screen like that. Those are the worst sessions, falling into that kind of self-googling. Resist, resist.

- Back your work up religiously. And irreligiously. And whatever other adverb is going to make sure you don’t lose your work. And don’t trust autosave. And don’t trust the cloud. Keep multiple copies in multiple directories on a variety of machines. Email files to yourself sometimes. To all your accounts. To your friends as well. And maybe to your enemies. Hit print on the whole thing every now and again. It’ll save you. Hopefully you won’t need it, but you will.

- Writing gets in the way of everything. But at the same time, if you don’t write, it comes out anyway, and leaves you lying in its trail.

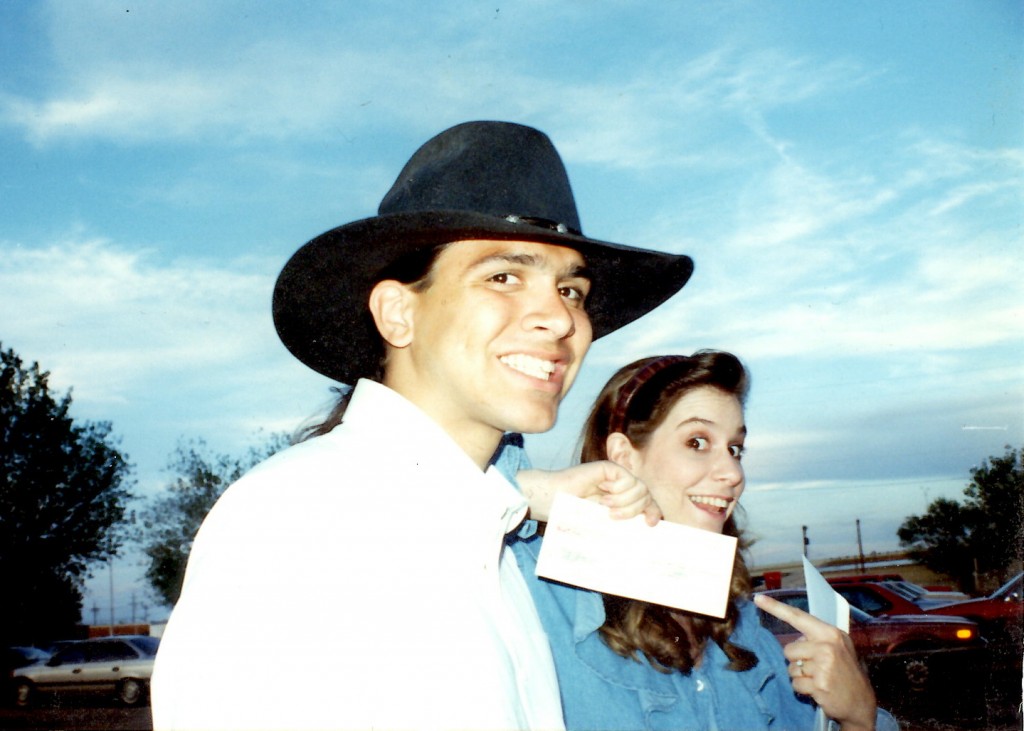

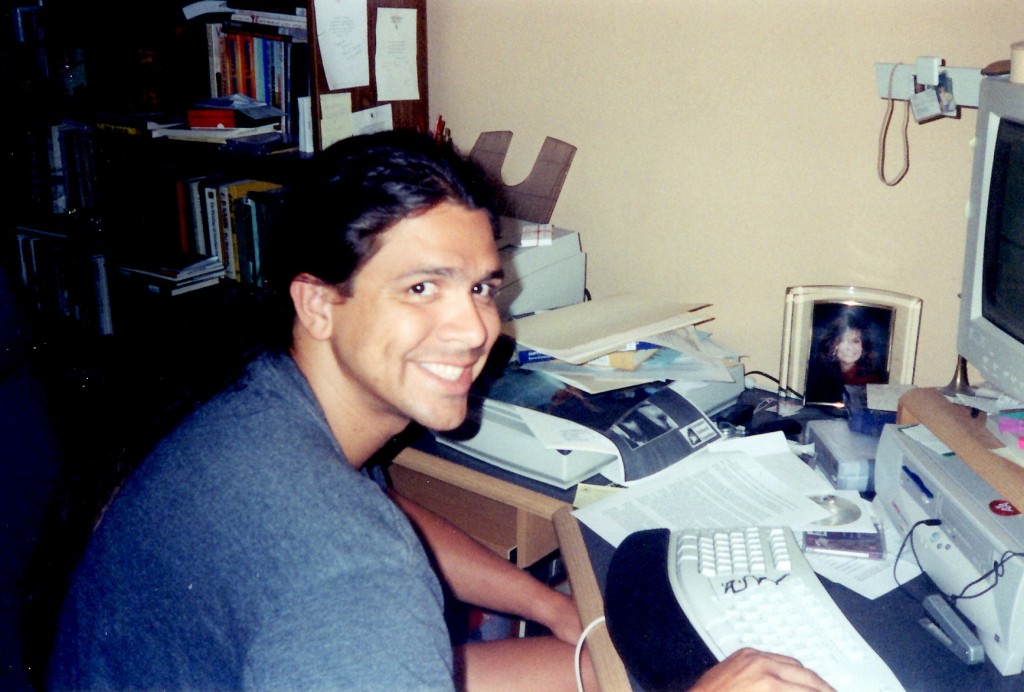

- Don’t take pics with your shirt off. Which is to say: don’t let your shirt be off when pics are being taken. Of you. This is advice straight from Peter Frampton, too, so I trust it. He says you only regret it later. And, there’s so many versions of ‘no shirt,’ right? There’s the author-photo version of the glamour shot. There’s the way the publisher wants to market you, so, say, people really into leopards are going to automatically key on you. There’s photoshopping to erase the years. There’s selfies that were so perfect you had to use them. But sometimes it’s better not to look perfect. Sometimes it’s better just to look like your own stupid self:

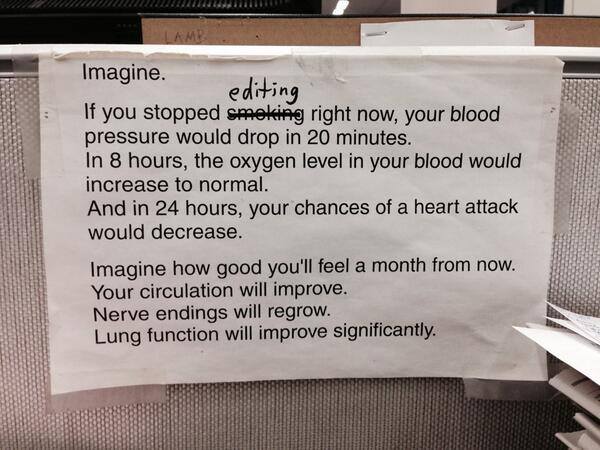

- It’s nobody’s fault but your own if your novel doesn’t chart. You can blame poor marketing, uncharitable reviews, the publishing climate, your secret nemesis, your actual nemesis, and you can hate everybody you want, but it finally comes back to you needing to have written better. Every day when I step into my office, this is what’s on my door, to remind me:

Demanding (or wishing for) a place at the table of high culture is an admission that you don’t have one; the way to get a place at the table of high culture is to pull up a chair and say something interesting. — Douglas Wolk

And, if I’ve learned anything else, it’s just to always read outside what you think your area of interest is. And to read books you fully expect to hate. And to reread books that hit you hard when you were fifteen. And to stop reading any book that you’re not enjoying, including (but hopefully not limited to) mine. Reading should never be a chore. A challenge sometimes, sure, maybe even a worthwhile slog. But not a thing you dread.

Also—but I don’t know how to teach this—learn who to trust. I’ve been with good publishers and bad publishers, crazy editors and editors who are a writer’s dream, and all kinds between. Some are my friends. Some are people I send manuscripts to for their opinion, even when I’m not going to be submitting it to them. And some still owe me big chunks of money. But the only way I learned to tell good from bad, it was by jumping all the way into the pool and splashing around. Not just dipping a toe in to check the water. You can’t know anything from somewhere safe. I’ve done commercial and I’ve done indie. I’ve been on national tour and I’ve also seen books kind of blip instantly off the radar. I’ve read to six hundred people one night and five no-eye-contact people the next. I’ve learned that marketing and distribution are so, so paramount, but so is quality representation. I was with the same agent for fourteen years, happily. Though we’ve parted ways recently, it was nothing bad, except I won’t be talking to a friend quite as much anymore. She never once let me sign anything that wasn’t bulletproof, though—well, when she could catch me before I signed, anyway (and sometimes you’ve already signed in your head by the time you’re asking people for advice . . .).

But, aside from the professional, you’ve also got to learn to balance the personal: family, friends, other work. All of which I’ve been extremely lucky with: a family that supports this bad habit of fiction, and a job that leaves me time to feed my addiction. If only I could stay out of the emergency room, or ever buy a big ridiculous truck that didn’t instantly become a money pit, or keep from always spending all my money on boots and bows and knives and fancy ridiculous shirts, then I’d have nothing to ask for, really.

Well, except for a Bandit-black Trans-Am. But someday, Clyde. Someday.

This is brilliant. Thank you for this, Stephen, for all of it.

This is the best. Sad to say I’ve never read your fiction, but I’ll be remedying the shit out of that tonight, for sure.

Thank you for this. I enjoyed reading it ~ some things are new that I never thought of while others are a great reminder.

Yes, thank you so much for this. All of this got me thinking about ambition. The thing about ambition is you either have it or you don’t. And if you have it it’s like life telling you: this is what you need to do. It’s so easy to hesitate about your ambitions and motivations but then, if you’re lucky and the timing is right, a reminder such as this post pops up and suddenly the mist is lifted. To me you’re like the living embodiment of ambition, man. I love your drive.

this is a great post, thank you.