First, to get the associations out of the way: the two movies this title kickstarts in my head are Strangeland and Adventureland. Anybody else the same? And that’s not bad. Anything that brings Dee Snyder to mind is a good thing, I say. But, of those two, Joyland‘s a lot closer in content to Adventureland. Except, where Adventureland was all nostalgic for the eighties (and expressing that through music that wasn’t my eighties), Stephen King’s Joyland is set in — I’m guessing here, as the first thing I did when I finished with my copy was loan it out — 1973.

First, to get the associations out of the way: the two movies this title kickstarts in my head are Strangeland and Adventureland. Anybody else the same? And that’s not bad. Anything that brings Dee Snyder to mind is a good thing, I say. But, of those two, Joyland‘s a lot closer in content to Adventureland. Except, where Adventureland was all nostalgic for the eighties (and expressing that through music that wasn’t my eighties), Stephen King’s Joyland is set in — I’m guessing here, as the first thing I did when I finished with my copy was loan it out — 1973.

And, to get something else out of the way: yes, when I was asked what book I’d like to be buried with, it was It — could there be any other? — but, too, when people ask what my favorite King novel is, it’s always Lisey’s Story. So, this was of course cool:

Anyway, to finally talk Joyland: needless to say, it’s solid. The last decade or so, King’s been writing with a sureness that never quite leans over into that kind of authority that a lot of writers assume late in their career. Which, I mean, no, nobody’s had a career like him, so comparisons are tricky, but still: Updike, say. He was king of The New Yorker set, yes? And you could tell by the way he wrote that he knew that. I never feel that same sense of presumption, reading Stephen King. Or listening to him speak, either. It’s not just nice, it’s a model more writers should pay attention to.

And, no, though Joyland has a ghost, somewhat, and a kid Professor X, this isn’t Pet Sematary never-sleep-again horror. This is a Hard Case book; it’s about crime. But, like all of King’s work, going back to the beginning, it’s really about people. I’ve tried and tried to figure out what exactly he’s always had that set him apart. I mean, a lot of people say luck — to which I guess I would answer ‘sixty-some-odd books of luck?’ — and some people say timing (which, isn’t that ‘luck?’), but the people who really read him, at least the ones I talk to, they tend to agree that the way he pulls you into his brand of horror, it’s by writing these real, engage-with-able people. People we root for, people we hate. In Joyland, that’s Devin Jones, a twenty-or-so-year-old guy just trying to figure out life, and his place in it.

In true crime fashion, then, sure enough there’s the mystery of the dead girl — eventually solved in a very cool, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo way — and there’s all these red herrings swimming around, grinning like each of them definitely did it. And there’s the amusement park, which is a character itself here, and done with such detail that I’m already remembering it as a real place. In the afterword, King says he used some reference books, but — and this is the mark of a job well-done, a story well-told — of course I know he’s lying. In 1973, barely pre-Carrie, he had to have moonlighted here, soaked up all the details, the atmosphere, the tone, and is now using reference books to pretend it’s all made up.

Right?

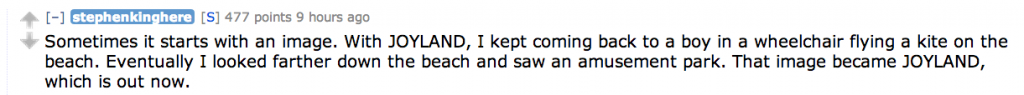

Anyway, I’m realizing now that I’m ducking the finer plot-points, as I don’t want to spoil it for you, but, come on: the way a good story works, it’s that you can’t spoil it. Because it’s not in knowing what happens. It’s in experiencing it as it happens on the page. The magic’s in the telling, not in the synopsis. And it’s in the images. Which, to go back to the same interview, is where it all started for King with this one:

Too, with King’s body of work, I wonder if, when he floats a kite up like this, he knows his whole audience — the whole world — can already hear a big truck barreling down that two-lane? But then he throws it up to the sky all the same. And we all look, and we hold our breath, and it keeps going, and we trust him to hold that string for us again.

____________________

(one of my students, beating me to a Joyland write-up)

(also, if I knew where/how, there would be a Doctor Sleep countdown-timer right exactly here: _______ )