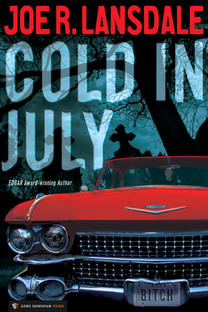

The trick in adapting a novel—or anything—for the screen, it’s not about being loyal to every line or faithful to each scene exactly as it happens on the page, it’s about identifying the beating heart of the novel, and then finding a way to get it on screen such that the final effect can feel the same. Jim Mickle’s Cold in July does exactly that with Joe R. Lansdale’s novel Cold in July, a book readers have been celebrating now for twenty-five years. After this movie, though, I imagine there’s going to be a whole new set of readers coming to this book, and then falling into the rest of the Lansdale shelves. And that’s plural on purpose, there. I envy them their fall, too.

The trick in adapting a novel—or anything—for the screen, it’s not about being loyal to every line or faithful to each scene exactly as it happens on the page, it’s about identifying the beating heart of the novel, and then finding a way to get it on screen such that the final effect can feel the same. Jim Mickle’s Cold in July does exactly that with Joe R. Lansdale’s novel Cold in July, a book readers have been celebrating now for twenty-five years. After this movie, though, I imagine there’s going to be a whole new set of readers coming to this book, and then falling into the rest of the Lansdale shelves. And that’s plural on purpose, there. I envy them their fall, too.

And, what’s surprising with this adaptation, it’s that, while it didn’t have to be faithful the novel, still, just about everything that happens on-screen, it’s lifted from the page. Sure, there’s some things condensed, some characters erased, but that’s just because the conventions of film and the conventions of fiction are different. That beating heart, though—let me get at it sideways, so as not to directly spoil: you know how the real pleasure of zombies, in both videogames and movies, it’s that they’re complete monsters, you can’t negotiate with them, there’s one and only one rational response to them looming over you? Shooting a zombie feels so righteous.

That’s exactly what Cold in July is about. It’s about putting a normal, small-town guy in a situation where he questions his own response to protect his family, and then sending him on an adventure where he’s shown that his response to protect, it’s not only right and reasonable, it’s a duty. Any ethical hesitation is erased. We’re even cheering his response, and wishing we were him the same way we wished we were William Wallace in Braveheart.

Where Cold in July really accelerates past the Bravehearts, though—and the movie does preserve this as it was in the novel—it’s by texturing this whole dilemma with fatherhood. No, not texturing: tying it in directly, and showing fathers and sons from different angles, yet never resorting to homily or sentiment. This story doesn’t take the easy way out even once. As Lansdale himself says right before his most well-known story starts, this is a story that doesn’t flinch.

And, for all the longtime Mojo readers, there’s even nods to some of Lansdale’s other works. But I’ll let you see them yourself.

What was really telling about the movie for me, though, it’s that my wife and I sat all through the credits talking about it, and about 1989, which was rendered pretty spot-on, even down to the excellent final song (hint: White Lion). At one point my wife said, about the pacing, that “it was so Joe.” And she’s so right. Lansdale’s got some of the best instincts around for the rhythm of storytelling, and where to inject humor, when to cut some gore you’d really rather not have to see. And, with a cast like this—Michael C. Hall, Sam Shepard, Don Johnson—of course all the acting’s more than spot-on. But the camera work and the set design, that’s what really sells this one for me. The composition of each shot is so intentional if you really watch, but it never gets in the way, either. It makes you appreciate film, I guess I’m saying. Yet never at the expense of the story. All adaptations should have such a steady hand.

And, not really talking location, but tone: Texas. In his introduction for Preacher, Lansdale notes (rightly) that, while Ennis tells a good and crazy story set in Texas, still, this ain’t Texas, not by a long shot. Cold in July, though, it’s Texas through and through. I’m not saying it was shot in Texas—I think I knew at one point, but have forgot—I’m saying that it feels like Texas. The same way A Perfect World did, or Sugarland Express. That’s partly due to the story, of course, and the characters, and their rambling outside the lines of the law—Texas stories generally put justice in the hands of the individual, not the courts, and that’s a big part of why we like them, I suspect (that’s a great fantasy to buy into for a few hours; it’s every western, from Zane Grey to Louis L’Amour)—but there’s something else, something hard to pin down. Whatever it is, Mickle gets it right. It’s not Don Johnson’s cool shirts, though I think I’ve got matches to most of them in my closet, and it’s not his red Cadillac, but I guess it kind of might be the mariachi in the restaurant, say. Or plinking bottles in the back yard. Or feeding leftovers through the hogwire. And it’s the way our hero and his wife sit on a couch together. It makes me miss home. But, luckily, there’s novels and movies like Cold in July, that can take me back for a little bit.

If you’re close enough to catch Cold in July on the big screen, then of course do that. If not, though, then it’s streaming. And—maybe this was just for us—right when it started raining in the movie, the skies opened up above Boulder, too, so that the sounds mixed and we couldn’t tell one from the other. I can’t guarantee it’ll rain on you if you cue this up, I don’t guess. But I can guarantee you’ll be lost in a good story.