this originally posted over at the now-dead Depraved Press back in February 2008. Had completely forgotten about it, but Jesse Lawrence, the “JL” here — you’ll also find him in various acknowledgements and thanks in my books — hadn’t forgot, still had it saved in email. However, all the formatting’s gone, with this paste-across, so, much as I hate it, no italics for the titles. As of now, anyway. But all the words are the same

JL: You wrote your first story whilst in the ER waiting room. What was the story about? Has it been published?

It was called “The Gift.” This would have been 91 or so, I guess. Maybe 90. It’s about a guy walking through this neverending snowscape, going, you know, to some surprise place. But I don’t want to ruin it — I mean, any more than my writing then already does. And no, never published. Don’t think I ever submitted it anywhere. My first published story would be this story with a parrot in it, and a glass ashtray, I don’t remember the title, but it was in this student mag Mindpurge. 1994 or thereabouts. Or, no, it could have been this story about a great dane and a burglar, locked in a cellar, “Two for Breakfast.” Man, I don’t know. As for “The Gift,” anyway, I think I found an electronic version of it a while back, PDF’d it, slapped it up somewhere on my site. Oh, too, this reading I did a year or so ago, I’d forgot. The woman was there, way in back, who I’d first given that story to. Who, I mean, she then gave it to the creative writing faculty, and here I am now. Crazy. Anyway, she remembered this “Gift” story, and still had an ancient, yellowy version of it, the main version, I guess, before I thought I could make it better. Which is where the story takes the predictable turn, yeah. I have no good idea what I did with that copy she gave me, though I did stumble across it a month or two ago somewhere — it’s old enough that it looks like tea was spilled on it, then dried, leaving the paper all crinkly — and did that thing where I say ‘Hey, that reading I did a year or so ago,’ etc. Too, “The Gift,” it’s a love story. Which I’m finally starting to get back into writing some, after all this time. You listen to as much Charley McClain as I still do, you get kind of sentimenal, I suppose. Or I’ll use that as my excuse, anyway.

JL: Your first stories were published in 1997 and your first novel was published in 2000. What propelled you to write a novel? What was the transition from short story to novel like?

Black Warrior was 1997? Wow. Guess so though, yeah. I love that story and I hate that story. It’s a watered down version, or kind of like side-room, of this other story I’d been writing from every angle for a year or two then, “The Ballad of Stacy Dunn,” that got published in a student journal there at North Texas, I’m pretty sure. As for what got me to write a novel, it was lying to an editor. But this novel, that finally turned into The Fast Red Road, it was just like welling up. I was filling this three-ring binder up with sketches of or for it. Just couldn’t stop. I still have that binder too, and it’s freaky to go through. I mean, the book was so different then, was about this guy kind of chasing this ghost circus, and finally, the only way he gets to it is he steals this eighteen-wheeler and drives under a fallen-down bridge, that looks like it kills him, until he does the Terminator 2 trick, sits back up, only he’s a ghost now too, I think. It also involved a lot of sections which were messages left by this human extremophile ‘Golius,’ these verbal monographs on the main character Pidgin’s answering machine. Just playing with exposition, I think. In a very necessary way. But the shift, from short stories to novels, it’s big, yeah. Just for anybody, any writer. You figure out you can go the distance, I mean. Which, yeah, sounds like I’m privileging the novel over the short story, following Joyce’s Dubliners-as-practice-then-the-real-work model. I mean, not at all comparing myself to Joyce here. Just saying he kind of, and not on purpose either, I’d guess, laid down a pattern which the whole twentieth century seems to have followed, which finally sets the novel in some way above the short story, as a more, I don’t know, ‘complete’ art form, something like that. But that’s not at all the case, I don’t think. And, that ‘completeness,’ it likely has to do more with the reader’s investment, which, instead of being measured in effect, gets measured in time. Like, if a novel takes a week and a short story takes a lunch break, then the novel must be worth more. It’s not about commodity, though, or displacement. It’s about impact. About what the story does to the reader. For me, say, yeah, Where the Red Fern Grows, man, it hit me hard in the fourth grade, and is probably what first made me think I could do this writing thing. But what I think about now more than Red Fern, it’s that old Gina Berriault story “The Stone Boy,” about these two brothers going to pick grapes at dawn or something, and the older brother getting killed on accident, and the younger brother going on to pick grapes anyway, because they’re easier to pick at dawn. For me, that kind of like pulled back the curtain and showed me just the shimmery outline of the essential strangeness of this being human thing. And, everything I read, and everything I write, that’s what I’m still looking for. But none of that’s really what you asked. Okay. It was terrifying, going from the short story to the novel. I immediately figured out that the essential question is What Comes Next?, and it’s the question you’re asking with every sentence. Unlike a short story, which I’d always been able to fake my way through, like I’d seen something running in the tall grass, and just had to chase it down for a few pages. The story-as-armadillo model, yeah. A novel’s not like that for me, though. With a novel, you understand that whole butterfly effect thing so fast. What I always tell my students about novels is that all you need to do, starting out, is have at maximum three things you kind of think might happen. Because just those three things, they compound, and get so complicated, and splinter into thirty things each, so that by the end you’re just scrambling, trying to tie it all back together with a neat-enough bow, or at least some kind of recognizable knot. Anyway, the way I dealt with that question the first time around, with what was coming next in Fast Red Road, was, instead of sitting around and thinking what would be best, what would contribute most to the effect or whatever I was going for, I’d simply, each time I hit a wall, or found myself teetering at that lip, a whole lot of nothing yawning down below me, was I’d mine all-what had happened to me. So, like, that woman who tells Pidgin that she could be his mom, that’s me, lost down in Carlsbad at five years old, this frosted blonde woman finding me somewhere, leaning down to tell me that. And how I ran away. And Birdfinger, Pidgin’s uncle, how he’s Pidgin’s dad in all the ways that are important, that’s my uncle. And all the trailer house porches that get stood on in important ways, those are my old trailer houses, those are the porches I grew up on. But yeah, what’s new here, saying first novels are autobiographical. With me, anyway, they all are, really. Just can’t seem to help it. They all look so transparent to me.

JL: Do you prefer one over the other – novels or short stories?

Novels. However, novels fail a lot more than stories, I think. With stories, you can access the magic just a lot more direct. Sometimes you just accidentally plug directly in, get so much more juice than you’d planned on. But that’s just an afternoon. A novel can take six weeks or two months. And what makes them better for me is that, for three or four days after they’re done, I feel good, I feel complete, I feel finally empty, like I can matter, I can take part in the world, do something good. But then on that fifth day or so, another novel starts whispering to me, and it’s back to all the bad places again.

JL: When you have an idea for a story, are there any indicators that it will be a novel or a short story?

Yeah. Short stories start with a line, with a way of handling exposition with voice, with a vantage point which is the only one that would work for telling this thing, whereas a novel, it’ll be in my head and I’ll think it’s just a little folded up piece of paper, but then I unfold it and find that it needs more unfolding, and more, and more, until it’s origami-ing out my eyes and my fingertips and I’m dreaming it and can’t stop writing it and have wholly lost any distinction between it and not-it. A short story, if I lose the voice a few pages in, screw it, I’ll scrap it, so what. It’s time to go watch some Magnum p.i. A novel, though, if I lose the forward motion there, then I’m going crazy for a week, because it’s still talking in my head, and I need to find the right way to get it on the page. No idea what’d happen if I never found that way to write it down.

JL: Have any of your novels started out as short stories?

Yeah. This one I’m calling, this week, Hair of the Dog, though it’s got about ten more titles as well, most recently, Bury Me An Angel. But my agent’s good about telling when titles suck. And I suspect that second one does. Anyway, it was a sixty-page story. But then, rereading it, I realized that there was another three hundred pages between the second-to-last line and the last line. So I just filled it in. Too, this was the only novel I’ve ever written that just made my physically sick each time I sat down to the keyboard. It’s just so over-the-top violent, or depraved, or something. Like it has no remorse for the stuff going on in it. I hated writing it, but would have hated worse to have not written it.

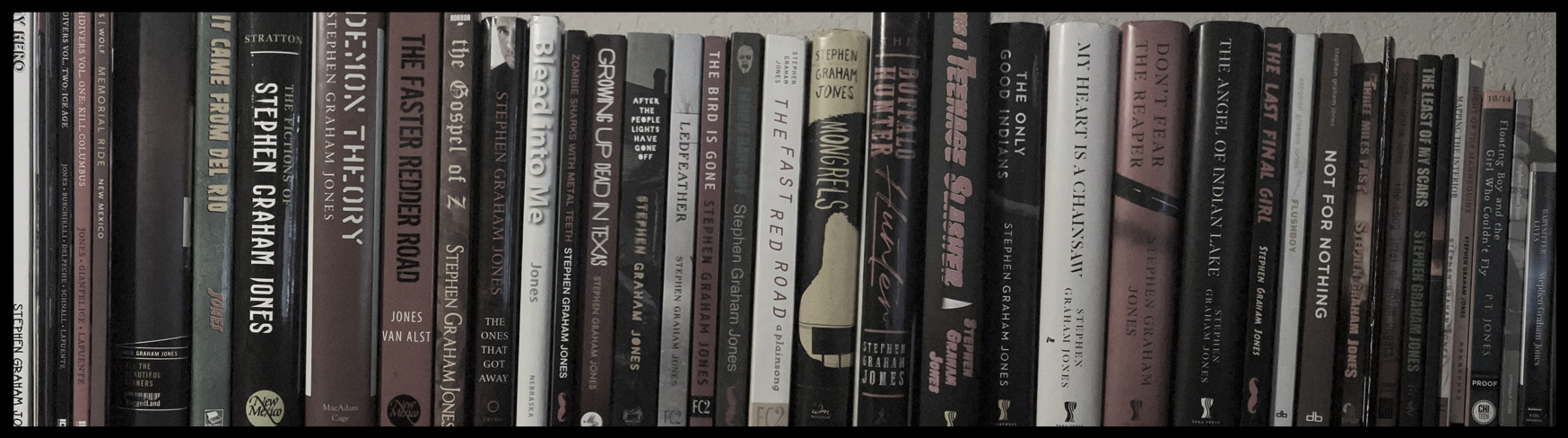

JL: You have one published collection of short stories, BLEED INTO ME. How or why were these particular stories chosen? Were they selected by you or by the publisher?

I selected them. As for why, yeah, that was the hard part, the part that nearly melted my brain. I had to find which set out of all these stories had something common between them. Not theme or content or voice or anything like that, and not when I wrote them, and not so much quality either. Just something that I can’t really articulate. They just went together. I mean, okay. I think the way I finally made a group of stories was I selected my three or so favorite stories, the stories I thought were strongest I’d ever written, then pored over the rest, seeing which went with one of these three. Then I compared all the stories that went with the main stories, and it kind of turned out that one group was a different collection, really. One that’s still not quite complete. As for which two stories survived, like team captains, I’m pretty sure it would have been “Carbon” and “Venison.” I wanted stories that weren’t about craft, weren’t about me showing off how I could shine some prose, how I could pull of this narrative trick, all that. I wanted the stories that had surprised me, that I was afraid to touch again, for fear I’d jack them up.

JL: Of your short stories, do you have any favorites?

Probably “Carbon” and “Screentime” and “Venison” and “The Ones Who Got Away” and “Jumpers,” that nobody ever likes, and “The Many Stages of Gried,” which is a lot truer even than “Bestiary,” and this unpublished “Little Lambs,” and “Father, Son, Holy Rabbit,” which I was looking for the other day in that Cemetery Dance it came out in, but of course, no surprise, I seem to have lost the magazine. Means either I gave it away to some random person in some anonymous hall, or that I left it on a table or bench somewhere. Or folded it in my pocket as I tend to do, and it fell apart. I don’t know. I need to get another. I like that story.

JL: You’ve had pieces published in various journals and magazines as well as online. Do you have a preference? Do you think the printed word has any power over the electronic one?

Printed’s cool because you can put it on your shelf, but I’d guess on-line lives longer, gets passed around more. I don’t have any real preference though. Why I do both, I suppose.

JL: Are there any publications you’d really like to see your work in?

Fantasy & Scienc Fiction. Weird Tales. Tin House. Backwards City. Anything with an intergalactic subscription base.

JL: Have you ever written or had the desire to write nonfiction?

That “Bestiary” piece is as close as I’ve come to non-fiction, but’s it’s not even close to being an essay. But no, I have no desire to write real non-fiction. I have a very strong desire to write fake non-fiction, though. Which I guess is just fiction, yeah? Anyway, I have this whole fake non-fiction novel plotted out, for once — usually I’m not much for mapping — but just need a summer or so to get it down on paper, now. Though I also have this epic-sized werewolf novel to get down, too. And I’ve got the most absolute perfect title in the world for it. So perfect I’m kind of even afraid to write the novel, I suppose, because how can it match up? Man, but then too I’ve got this other novel all ready to write, this for-kids novel about Santa Claus. I don’t know. I’ll probably write something next that’s none of these.

JL: When you wrote FAST RED ROAD, did you have in mind any conventions of Native American literature that you wanted to challenge or change? What are your views on modern Native American literature?

Yeah, all of them. I wanted to undo House Made of Dawn, the formula it laid down, that was and is just getting stamped onto the page and into the reader over and over again, that returning to the community is automatically a good thing. In Fast Red Road, that returned-to community, it’s fake, it’s stupid, it’s plastic, there’s nothing ‘automatic’ about it. I mean, I guess what I see as the main problem is that the American Indian Novel’s gotten so paranoid about cultural appropriation that it’s allowing essentialism in the back door. And that essentialism, man, it’s setting up house, cocking its muddy-ass boots up on the table and changing all the channels on the tv. Somebody needs to drive a truck through that living room. Preferably a red-on-white 69 Ford . . .

JL: Your novel BIRD IS GONE: A MANIFESTO is comprised of various texts or narratives. Is there a central theme and how do they relate to it?

Yeah, Bird’s such a sentimental novel for me. LP Deal’s just a pure dreamer. But it’s a defense mechanism for him, of course. He even tells the novel in such a way that it ends happy, with him stepping out of that van at sixty or whatever miles per hour. Man. Most days of the week, Bird is the best I can do, or ever will do. And that “Roses are Red” chapter is the best of Bird, for me. Everything I’ll ever be or do or want as a writer, it’s in that chapter, I think. Or in that first Indian on the moon there, whispering ‘gold’ back through his headset. I’ll never get over Bird. Or Demon Theory, which is kind of just Bird, but with all different pieces.

JL: How exactly did you keep everything straight while writing that book?

I have no idea. It was ridiculous. I would stare at the words on the screen until they swam into my eyes the right way, their sides flashing, and then I’d be LP, talking into his wrist, making this all real. Or, real enough. I’ll never be able to do anything like Bird again, though. It’s a kind of pure I don’t have the muscles for anymore. And that itself is likely a defense mechanism. Self-preservation, at least. What’s that old thing? . . . ‘a man can only speak like this once in his life, and even then—” but I lose it. Always.

JL: You’ve written about genre and its use in telling a story through particular conventions. DEMON THEORY, your most recently published novel, was actually the second one you wrote, correct? Did you plan on specifically writing a horror novel? What sparked the idea for it and how did that end up being a novelization of a film trilogy based on a book based on the case notes of a psychiatrist?

Yeah, Demon Theory was my second-ever novel, written just right on the heels of Fast Red Road, and meant kind of as its antithesis, so I wouldn’t get labeled an ‘Indian writer,’ which is just a way of allowing people to ignore you. Not because of the ‘Indian’ part, but because of the label, because of any label which is supposed to limit what you can write next, and next. And yeah, I planned on Demon Theory being horror. Or, to say it different: I wanted to write about what I love, what I felt I owed the most to, and that was, and is, horror. But no, I didn’t plan on all the layers in it, on the narrative being so stacked, so embedded, so much the result of some conscious and even aggressive line-breeding — beef-fed-beef all over again, yeah. But these things happen. In 1999 I probably didn’t know yet that I was only supposed to plan on having three things go on in the novel. Or else I mis-heard, thought I was supposed to jenga three parts together in some unlikely way that felt perfect.

JL: Have you ever set out to write a piece in a particular genre?

Once, yeah. I tried to write a sword & scorcery piece. Which is a genre I owe just a whole lot to as well. But the story pretty much sucked, was just me writing instead of a story getting told. But the fantasy landscape, it’s been so staked out. Or, I’m so aware of it being staked out anyway, that I have a really hard time operating in there. Then of course reading books like that The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, that doesn’t really help at all. But still, I have plans, hopes, dreams, all that. And they involve elves.

JL: Are there any genres you prefer to work in? If so, what draws you to them?

My goal, still, is science fiction. Just because it can instill a sense of wonder in the reader that can, on a good day, on some perfect day, let that reader think that the world’s a bigger place, a better place. That it’s magic. However, yeah, horror, that’s where I go nine times out of then. Wish I had some clue why.

JL: Okay. You’ve written some horror pieces so: what scares you?

People with dog heads.

JL: DEMON THEORY is broken into three parts. The first one feels like a slasher and the second a monster movie/story. To what would you liken the third?

Cool you picked up on that. My idea was to cycle from slasher to closed-door monster to haunted house. Like the first two were kind of ‘haunting’ the third. Seemed a natural way to iterate.

JL: ALL THE BEAUTIFUL SINNERS seems like your take on a thriller. It includes varying degrees of investigation as well as pharmacology. What kind of research did you do for this novel?

A lot, I suppose. I didn’t know much about thrillers when Rugged Land approached, signed me up to write a couple for them. So I inhaled just as many of them as I could, which was a lot, and then read, yeah, a lot of non-fiction type books on serial killers and all that — one of these, even, this Schecter book from the public library, was just packed with all this cut, black hair. Kept falling into my lap every time I turned the page, until I got pretty sure I was being set up for something here. But I read it all. And more, and more, I can’t even remember titles, except that, every time now I drink a Vanilla Coke, that feeling of writing ATBS kind of wells up inside me, and I’m hearing Bonnie Tyler in my head and I’m standing in my back yard watching the storms roll in in March and it’s pure, unadulterated magic. Of all the novels I’ve written, and even though a lot of the editorial process wound up getting pretty combative, which shows in the text, I think, still, ATBS was by far the best one to write. I doubt I’ll ever have a writing experience like that again.

JL: Your old bibliography lists a screenplay entitled STAY. What was the premise behind that?

I so love Stay, and keep trying to turn it into a novel, but haven’t found the right voice yet. Maybe never will. Anyway, it’s, first, I suppose, just me wanting to have gone to Journey concert in 1984. Too, it’s about the first guy executed in South Dakota in forever, and his daughter’s Billy-Jeanish crusade to keep that from happening. And the story for this one, it’s as pure and unjacked-up as anything I’ve ever written, I think. But it sucks as a screenplay, at least the way I’ve got it done now, and, like I said, wish I could make it a novel, preferably a short one. Maybe someday, when I’m better, more agile, all that. Or, less agile, really. I love the subsections for Stay, though. “My New Favorite Commercial,” “I Need a Hero,” “Don’t Take Me Alive,” “My House is Glass,” “Don’t Take Me Alive, Part II,” “Call Me By My Trues Names.” I think there’s one more, too. Anyway, I jammed this down on paper the first time on 01 or 02, so you can see I was in that ATBS mindset, all Steely-Dan’d and Bonnie-Tyler’d. And that “My House is Glass” is just a direct rip from this story William Cobb wrote fifteen years or so ago now, I guess, that showed up in . . . Motel Ice, maybe? Was that a journal? Reading that story, though, I’ve always thought that whatever that thing is in your head that clicks over, from non-writer to ‘maybe,’ that that’s when it clicked for me, and the world just looked all different then. Cobb, really, of all the writers I’ve read, I mean, half the stuff I write, I feel like I’m just aping Pynchon or PKD or King, maybe reaching for something Lem-like in my less intentional moments, but still, I think Cobb’s been about my biggest influence. His stuff just absolutely works for me. The prose is true, I mean. And I can’t think of anybody else I’d say that about.

JL: How do you feel about writing screenplays versus novels or short stories? Does your approach change from one to the other?

I think my approach is supposed to change, but, well. No. I think I tend to just see a screenplay as a way to tell the same story as a novel, just it’s shaped different on the page. But that’s not the case at all. Someday I’ll figure that out in a way I can actually use. Maybe. But of course that’s a lie.

JL: Also listed on the bibliography are some unpublished manuscripts. Some short story collections, some novels. I for one am dying to read SEVEN SPANISH ANGELS, a novel that Rugged Land was, at one time, going to publish (maybe BORN WITH-TEETH as well), so: are you still seeking publication on any of these? What are your plans for them?

I think we’ve (me and my agent) backed off on Seven Spanish Angels for a bit. Not sure why. I guess just because I have so much other stuff ready to go. But Seven Spanish Angels, I could read that novel fifty times, and it would still get to me each read. Marta Villareal. The story in this one, the way it develops — let me start over: I’ve rewritten this one so many times, more than any other of my novels, that it works on the page with no help at all, is like some little top that spins all by itself there on the table. And spins and spins. I love this book. And I so don’t need to be thinking about Marta right now. Or Elektra either, the main character from Stay. These are very dangerous places for me to try to step into and out of. They’re too sticky. I’ll never get out.

JL: Your next novel, LEDFEATHER, is due to be published in August. What can you tell us about it?

Well, ‘next,’ I don’t know. How about almost next? How about really-soon-but-probably-second-to-next? Can’t say anything official yet, though. But, Ledfeather. I just rehit it a day or two ago, then went line-by-line-by-line over it with my editor, and you’d think I’d be sick of it. But I’m not. At all. The ending here’s the second best I’ve ever done, I think. Or maybe the best. And the first isn’t published, is tacked onto this The Hedonist Chronicles novel I wrote which’ll rightly never see the shelf, so I guess Ledfeather is the best, then. Or will be. As for stuff about Ledfeather — have I said this somewhere already? Hope not. Anyway, and this likely doesn’t get me many good points, I suspect, but, after hitting Only Revolutions, I sat it down, kind of nodded or shrugged — I don’t know, I wasn’t taking notes that day, I guess, not about myself anyway — that that was cool, yeah, but then the shape of Only Revolutions kind of just bloomed in my head, these two V’s that kind of push into each other with their points, become an X almost, a narrative handoff, a ladderback spiralchain of life, and I thought, wait, you don’t have to do all this typographic stuff to pull that off, do you? Can’t you do it just with straight text? I don’t know. I think so though, yeah. You can do it. Maybe I can, even. Or I had to try, anyway. And, for kicks and grins, here’s the first line of the author’s note for Ledfeather:

This all started with a misheard Def Leppard lyric and a true and abiding love for June Morrissey.

That kind of explains my whole writing project, I suspect.

JL: I’ve read that you listen to music while writing and usually have something specific for each novel. What was LEDFEATHER’s soundtrack?

I can’t even start to pretend to remember. I’ve written a few novels since then already. And, just checked my playlists, and I have some associated with those novels – one’s called ‘jerkwater,’ for Flushboy – but if I had one for Ledfeather, and I’m sure I did because that’s what I do, I called it by some code-name, and I’ve lost that key. Happens about every day. Surprise surprise. Wait, wait. I did have a playlist, I’ve just retitled it, because it never got retired. Go over to wherever Litblog Co-op is. I might have pasted that playlist into a blog entry over there. Along with some Frank Frazetta, aka he who makes everything better.

JL: You also teach. Currently in Texas, but you’re reloacting to Colorado. What will you be teaching there?

Mostly fiction, and, you know, the writing of it. Maybe some lit, too, who knows. Just all over the board: post-apocalyptic, haunted house, American Indian, the short novel, and on and on. Maybe even comics and graphic novels, if I can get over that hurdle of how to get the students textbooks without making them spend five hundred dollars.

JL: Have you ever used your own work in your lessons?

No. Though I will often submit my stuff to workshop, if that counts. Then assign somebody else as instructor for a bit.

JL: You seem to be a fairly avid reader. What three books do you think or wish everyone would read?

Don Quixote, The Magus, and FUP. And also It or Deliverance. And American Psycho. Oh, oh, and The Life of Pi. Definitely Life of Pi. And The Girl Next Door. Ketchum’s, I mean.

JL: You’re part of an online community called The Velvet which began as a website devoted to Will Christopher Baer and then grew to include Craig Clevenger and yourself. What do you think of these fellow writers’ work? Do you see any particular reason why the three of you would be grouped together?

Craig and Chris’s stuff just blows me away, of course. So polished, so precise. Like some exterminating angel’s passed his eye over each syllable, and said either Yes or No, never just Maybe. And all we see are the words that got the nod, of course. As for why the three of us are grouped, I’m not sure. I can see Craig and Chris’s stuff together, of course. Both content and style synch up, could go slouching off into that anti-sunset. I’m just lucky to hang out, I suppose. Faking it, like always. Smiling a fake smile and hoping nobody notices me.

JL: Now, the one question I ask everyone since Depraved Press is focused on media. What are your favorite books/authors, bands/musicians, and films?

I’ll read anything Christopher Moore writes, I’m pretty sure. Same with Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child. And King, definitely. And I owe more to Barth than I could ever hope to repay, and there’s times in Alexie’s stories where the world’ll recrystallize around me. And I like that.

As for favorite books, that can get out of hand just real fast. If I had to pick a favorite one ever, then it might be Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, I suppose. Though as often as not it’s American Psycho too. Or anything with Conan.

As for bands or musicians, it’s just, and always, Springsteen and Seger for me, with a lot of Waylon and Johnny Lee and Earl Thomas Conley besides. This week it’s been just a whole lot of Tesla and Cinderalla, I suppose, Billy Joel too, and Neil Diamond, and Morphine and Murder by Death, though for about three weeks there it was Don Williams just over and over and over again. And Roseanne Cash, I could listen to her forever. She says things in a way that just makes them true.

And, films, movies, I’m not much for the award-stuff. Give me some good horror-comedy any old day. Feast and Leslie Vernon and Idle Hands and Dead & Breakfast and Club Dread and Slither and Save the Green Planet and Severance and Black Sheep and Night of the Living Dorks and Psycho Beach Party and ReAnimator and Hysterical and Shaun of the Dead and Boy Eats Girl and The Murder Party and Scream, especially Scream, always and forever Scream, I would be incomplete without Scream. But also Life is Beautiful and Jacob’s Ladder and Lost Highway and Juno, yeah. And Doc Hollywood and Leap of Faith and Footloose and Die Hard and The Last Boy Scout and Henry Fool. But I’m going to get carried away here.

JL: Thank you very much, Stephen.

Thanks back.