1. Horror can still be very disturbing and very complete without gore and nudity

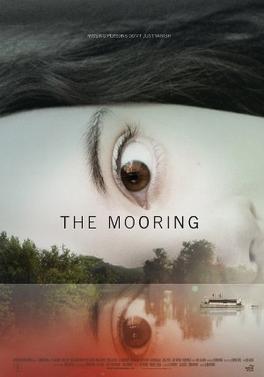

Is there even any profanity in The Mooring? I can’t think of it, if there is. Which isn’t to say over-the-top gore isn’t a complete riot, just all kinds of fun. I like it when I have to hide my eyes. Last time that happened, I guess, would have been Excision. First time? Probably The Exorcist. Well, okay, The Eyes of Laura Mars, but that wasn’t from gore, but absolute, undiluted terror; I was eight, I think. But, nudity in horror—for a long time the theory (or, maybe, just the practice?) was that it was enough of a pendulum swing the other way from gore that it allowed the visual palette of the film to achieve a kind of balance. Or is that just a rationalization? It could have been just as simple as the filmmakers knowing that, even if the story was thrown together and the production poor, there was still one way to lure their target demographic to the drive-in. One way that’s significantly cheaper than hiring a Tom Savini or a Kevin Williamson. And sometimes I think nudity in horror—in the slasher in particular—is just the director being all leery, taking advantage of girls fresh off the bus, as it were. It’s not called exploitation cinema for nothing. And nudity could even be setting the audience up to be punished, I suppose: if it’s thrilled when the clothes are peeled off, then what about when the skin is? Maybe you should have asked for that shirt to stay on, yes. Anyway, Scream got by without nudity, with just the suggestion of it (sexuality’s still important to the slasher, and there is some of that in The Mooring, albeit of the creepy kind), and a lot of others have as well, and are none the worse for it. But, yes, it is kind of built into the genre, I know, as the My Bloody Valentine redo makes very clear, in skintastic 3D. I prefer John Carpenter’s explanation over Carol Clover’s too. That axe-to-the-head, it’s not Jason punishing these people for having sex—what does he care?—it’s a single killer striking at the best opportunity: when people are distracted, and when they have no clothes, when they’re tangled up in blankets or seatbelts, and when they’re far enough from the group that their screams won’t be heard. And it’s probably night, too, making for an easy step back into those ever-important shadows. And, yes, the The Mooring cast is of course young, making nudity hardly an issue, but we’ve all seen beach and lake and river horror movies—even Kid Rock music videos—and know full well that half the time, the nudity comes from other boats. Boats that seem to be there specifically to display naked people. On the water, nudity’s always a bikini string away. For The Mooring to be set on the water and have no nudity, though—and be low-budget—it’s refreshing, it’s surprising. And it completely works.

2. Simple is always best

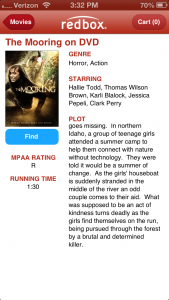

Standing at the Redbox, all you get of The Mooring is a single paragraph, kind of like a bloated logline: a group of teenage girls go on a no-cellphone boat trip, and it very quickly turns into Deliverance, into Wrong Turn, into Reavers of the Backwoods. And THAT’S IT. Most films, that’s just the hook; once you slide it into your player, things get significantly more complicated. Which isn’t always bad, either. With Cabin the Woods, we thought we knew the story, right? Then were thrilled when that was the surface, that was just the hook. However, sometimes there’s a message, and that’s usually not so great. I mean, unless the message is along the lines of “Maybe you should follow that curfew?” But slashers in particular (horror in general) (fiction in generaler) aren’t populated with characters who always make well-reasoned decisions. If they were, there would be no initial crime or prank—there would be no reason for a slasher or monster to ‘rise,’ punish the guilty. We love and need that cycle of justice, and even when there’s not supposed to be a message, there is: what you do, it comes back to you, like twentyfold, and in a mask. Just please don’t get didactic and soapboxy about it. Let us extract the message, if we want, and have any use for it. You don’t have to consciously pack it in, I mean; it’s built into the genre. But it’s perfectly okay to come to the genre just for the thrill, too, for the transgression, the roller-coaster ride, the screams, or to be in the dark with somebody. No worries, though: there’s no real message in The Mooring. It’s not against cellphones, it’s not against violence, it’s not against sleeping bags, and it’s not making fun of other slashers. And, to say it again, it’s just so, so simple: a group of girls go out on a boat, the boat breaks, then some crazy dude—best of his kind since Krug in 1972, I’d say—starts killing them all. After that, it’s just a chase, plain and simple. A game of survival, and luck. And, yeah, there’s redemption, but it’s hardly pure. Nothing like crawling up the front of that bad dude in Just Before Dawn, sticking an arm down his throat, getting reborn from that act, from that violence. The rebirth in Mooring, it’s much quieter, much sadder. What’s even better, you’ve known it was coming all along. And that’s the hallmark of a strong story: it’s finally not about what happens. You can’t spoil strong stories, I don’t think. And this is a strong little story.

3. Kids completely change the dynamic

Of the slasher, anyway. And, yeah, evil kids have been used to death in horror, from, I don’t know, Alice Sweet Alice to Children of the Corn. A great span of eight years there, yeah. Start it with Damien and cap it with Samara, then. You don’t get more evil than those two. But none of those evil Macauly Culkins (The Good Son? Anyone?) apply to The Mooring. No, much as the original Nightmare on Elm Street kind of promised, even if it cast plus-eighteen year olds, it’s actual kids who are being harvested here. No, ‘harvested’ suggests a later use, and that’s not the case here. It’s more just killing for killing’s sake. So, to back up: usually in a slasher, you’re excited when people start trying to catch machetes with their throats, right? They’re old enough they should have known better than to come out here. We even laugh, and cheer for more. Even in that second Jeepers Creepers, don’t we cheer when this phage-monster starts using the busful of kids’ bodies like a scrapyard? It’s because they’re not really kids, the same as they definitely weren’t in Happy Birthday to Me and all the rest. The Mooring, though, this boatload of, I don’t know, fourteen, fifteen year old girls, even if they’re not actually that age in real life (no clue), in the life of this movie, they definitely are—and, importantly, they’re not hyper-sexualized. They’re just kids. Our natural impulse, then, it’s to protect them, to, you know, have them NOT die. But this is the genre it is, of course. You don’t put your characters in a meatgrinder plot to protect them. And—that dynamic I was talking about above, that’s been central to the slasher nearly since it was born? The inciting prank, the act that gets this ball rolling, that kickstarts the cycle of justice. You know, like stranding that dude in bed with a corpse in Terror Train, or slapping that fisherman with a car in I Know What You Did Last Summer. There’s none of that here. Sure, one of these girls did cause a wreck (nothing like in Final Destination 2, alas; that wreck alone probably quadrupled the budget of The Mooring), but that issue’s dealt with nearly immediately. She feels bad, she writes a letter, case closed. Otherwise, they’re pretty much Regan, sleeping in bed, just being good, when BAM, the horror’s there, and it’s there to stay, sorry. Usually I’d consider this a flaw (see my write-up of the Prom Night remake), but, first, I think the slasher’s changing a little bit to better answer this new world it’s playing for, and, second, if there had been a prank, that would rub up against these ‘pranksters’ all being kids, so we’d be torn: do we want them to die and die hard, or do we want them to avoid the violence, effectively forgiving their trespass? Does their victim get justice (dressed as revenge), or not? The Mooring would have lost focus had that been the situation, I think. Instead, it kept it simple, and maintained narrative thrust, straight on till the end, when we finally take a breath, look around the room.

The final test of The Mooring, though, it’s whether it births its horror, Cronenberg style, into your world. And, as you can tell, there’s nothing supernatural here. Meaning The Mooring, it’s not trying to get us reluctant to turn the lights off tonight, or nervous about what world that closet might actually open onto. No, in The Mooring, as in Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door, the evil is people. The evil is us. And it does leave you with that, definitely. You don’t feel complicit after making it through those ninety minutes, but you do come out more wary, I think. About chance encounters. About strangers. About life.

And that’s not bad.