Don’t get me wrong, I love Demon Theory, I’m forever lost in it. But still, I always wondered what a novel written with that kind of syntax might look like if

somebody took out the footnotes. And then what if they also took out the screenplay language stuff? What would be left? Just straight-up story?

Zombie Bake-Off, pretty much.

To back up again, though: the big hurdle for me and graduate school, at the MA level anyway, it was that I had this big prejudice against dialogue. I felt certain you could tell and novel and tell it wonderfully by simply paraphrasing all the dialogue. Yet there are conventions, there are norms, there was, evidently, stuff to be hammered sidewise into my head, whether I wanted it to be there or not. And, no, Lord of the Barnyard hadn’t been published at the time. Had it have been, I’d have held it up as my standard, my proof, my defense: 402 beautiful pages, and never a quoted line of dialogue (no unquoted, either—all paraphrased, indirect). But, as things  went, I reluctantly started letting my characters actually speak on the page. Complete revolution for me. Then, a year or two later, I even started using actual real quotation marks. I was a complete sell-out of/to the person I’d been trying to be. But that’s growing up, too, I kind of suspect. If you don’t have any regret, any secret fondness for the way things might have been, maybe even should have been, then you’re still lucky enough to be a kid, and are probably going to live forever.

went, I reluctantly started letting my characters actually speak on the page. Complete revolution for me. Then, a year or two later, I even started using actual real quotation marks. I was a complete sell-out of/to the person I’d been trying to be. But that’s growing up, too, I kind of suspect. If you don’t have any regret, any secret fondness for the way things might have been, maybe even should have been, then you’re still lucky enough to be a kid, and are probably going to live forever.

People should be so lucky. I should have been so lucky.

But, dialogue: I was now a user of dialogue. My first novel, then, The Fast Red Road, it actually has people talking in it. Out loud, directly. And, what I found was that my profs had been right: fiction can be better with that vital element mixed in. So, something along the line of minutes after wrapping Fast Red Road, I sat down at my 386 to be this completely different writer. One who was now going to use onlyquoted dialogue. As in: none of it would be ‘internal,’ indirect, paraphrased, any of that. Demon Theory, yeah. I mean, I also wrote it because I was terrified of becoming an “Indian” writer—not that I’m not Indian, but adding adjectives in front of ‘writer’ is always a form of dismissal—which is to say I hovered my mouse for a long time in Demon Theory over that “Indian burial ground” line, as I’d been so trying to go three or four hundred pages and, very unlike Fast Red Road, never say “Indian.” But, finally, it served the story, the genre, all that, so I left it. But I never let any dialogue go indirect, get paraphrased. And the screenplay-language fun, it grew out of that almost immediately. Like, page two, if not faster. And then I went back and re-did page one.

All of which is to say that Demon Theory, as nakedly autobiographical as it always will be to me—it and Bleed Into Me each feel like that—at its beginning, it was kind of an exercise in dialogue. In how to get people onto the page in a way the reader could access. Or, how to get them on the page in a way the reader was already conditioned to access.

But, after Demon Theory—I wrote it in 1999, even though it didn’t come out until, what? 2005?—I also scurried as fast I could to a different place, a different mode. I didn’t want to somehow get known as the dude who always writes like it’s a movie he’s recording. Insert just a whole lot more novels here, all over the place genre- wise, style-wise, all that. But in there, and I can’t remember exactly when I wrote it, though I half-remember working on it in an office I had in 2005, was this It Came from Del Rio thing. It was kind of my version of a re-do of this Bloodlines novel I’d written in 2000 or so—a werewolf story set down in Alpine, Texas, a story very influenced by PKD’s The Galactic Pot-Healer—and, I say ‘re-do’ in the sense that I was using the same geography, the same emotional landscape. I was trashing Bloodlines in hopes I could revive it as something else, because no way would I allow myself to use the same terrain again and again. I’ll never be on of those postage-stamp writers, who can milk fifty books from a few acres. No, I’m there and gone. Kind of a principle. If I don’t keep challenging myself, why play, right?

wise, style-wise, all that. But in there, and I can’t remember exactly when I wrote it, though I half-remember working on it in an office I had in 2005, was this It Came from Del Rio thing. It was kind of my version of a re-do of this Bloodlines novel I’d written in 2000 or so—a werewolf story set down in Alpine, Texas, a story very influenced by PKD’s The Galactic Pot-Healer—and, I say ‘re-do’ in the sense that I was using the same geography, the same emotional landscape. I was trashing Bloodlines in hopes I could revive it as something else, because no way would I allow myself to use the same terrain again and again. I’ll never be on of those postage-stamp writers, who can milk fifty books from a few acres. No, I’m there and gone. Kind of a principle. If I don’t keep challenging myself, why play, right?

Anyway, Del Rio, me and my agent, we could come up with no way to pitch this. It just didn’t fit any of the ordained categories . . . of anything. But then, by hookand crook, and a lot of luck, this one place picked it up nevertheless, and the response has been very good. Could be readers—unlike bookstores—don’t need the marketing categories so much. They just need the wild stories. The, as Craig Clevenger put it, “rabbit-headed zombie chupacabra shepherd” stories.

Yet, Del Rio, though I wrote it something like 2005, maybe—2006?—it wouldn’t come out until 2010. But, with it, I really kind of felt like I was lucking onto something. That there was story to be mined in these in-between places. And, Demon Theory, it was still—and always will be—whispering in my ear. And, at the time, I was really enamored with closed-door horror stories, and couldn’t understand why all horror wasn’t being done that way. It just makes such good sense. I suspect it was The Murder Party that got me thinking like this, too (thanks to Jesse Wichterman for the heads-up on that one, forever ago). Back then I was still VHS, so watched it that way. Over and over and over, trying to plumb the magic. Like—the same way Will Christopher Baer says he reduced Reservoir Dogs to index cards, and laid them all out, trying to crack the code, that’s how I was, and am, with The Murder Party.

Like I say in the acknowledgements, though, The Poseidon Adventure played a big role in Zombie Bake-Off too. As soon as those doors get shut, that seems to be the only story that cues up. Which is good for me, as I never cracked all the way into The Murder Party, I don’t think. It’s got all these down times that I completely suck at. I just get instantly bored, want something to happen, please, and fast-like.

As it turns out, zombies, they’re a good and exciting thing to introduce to just about any scene. Big revelation, I know.

So, then, it was just a matter of where to have this story happen. And that was so easy: the campus I was on at the time, Texas Tech, it has a coliseum on it that had kind of been retired, was being used for rodeos and tractor-pulls and stock shows and hockey and circuses. Still, I’d walked the stage there to get my diploma, once upon a time. And I’d tried to break into it one night. And I’d been dragged out of it a different night, by too many police. I saw Rush there, I think, and a few other bands. It was a real place, I mean. And, when you’re pitting soccer moms against the undead, you kind of need a place you don’t have to make up. I did, anyway.

So, then, it was just a matter of where to have this story happen. And that was so easy: the campus I was on at the time, Texas Tech, it has a coliseum on it that had kind of been retired, was being used for rodeos and tractor-pulls and stock shows and hockey and circuses. Still, I’d walked the stage there to get my diploma, once upon a time. And I’d tried to break into it one night. And I’d been dragged out of it a different night, by too many police. I saw Rush there, I think, and a few other bands. It was a real place, I mean. And, when you’re pitting soccer moms against the undead, you kind of need a place you don’t have to make up. I did, anyway.

All I needed now was a hero. Somebody who thought zombies were completely stupid, and didn’t have time for any of this, yet had some issues of her own to be working through. Some issues that, say, fighting a whole horde of zombies might solve for her, somewhat. I needed a Ripley. And I found her, I don’t know how. She just kind of raised her hand when I looked out into the darkness for somebody.

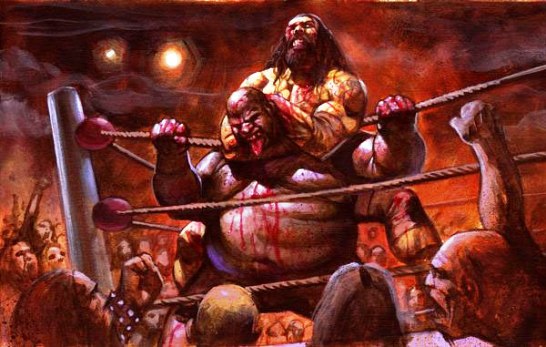

And, the wrestlers, man. One of my dream jobs has always been to be a racehorse namer, and this was the next best thing. Of course I’d grown up on Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage and all them—that first horror story I had published, that made it around, “Raphael?” I didn’t write it because I wanted to do something scary, I  wrote it because I wanted to write about G.L.O.W. (remember?). Zombie Bake-Off isn’t that different, finally: just as Demon Theory was a kind of love letter to horror, so is Zombie Bake-Off a love letter back to all those nights I spent waiting for somebody to slap their hand into the canvas, stand back up when it’s completely impossible to stand back up. If we all yell loud enough for them, I mean. If we all believe.

wrote it because I wanted to write about G.L.O.W. (remember?). Zombie Bake-Off isn’t that different, finally: just as Demon Theory was a kind of love letter to horror, so is Zombie Bake-Off a love letter back to all those nights I spent waiting for somebody to slap their hand into the canvas, stand back up when it’s completely impossible to stand back up. If we all yell loud enough for them, I mean. If we all believe.

I did believe. I do believe.

So, all the elements, man, I had them there on the table before me. Except, each time I tried fitting them all together, I’d fall into the lope of that Demon Theory voice, and I so didn’t want to be accused of being a one-trick pony (though I’m happy to even have one trick, I suppose). My solution, then, it was to split that voice off. To, right alongside the Zombie Bake-Off novel, scene-for-scene, write it as a screenplay as well. And, I’m completely and always in love with the screenplay format. I love the limitations, how hard it is to move in those tight, ridiculous confines, and how, no matter what perfect thing you create, still, it’s going to get changed and rewritten and noted to oblivion. I love that. It means you’ve got to write the skeleton of the story such that, no matter the flesh that gets slathered on, it survives, it persists. It’s the ideal challenge for a writer, I think. A few years after doing this, I’d do something like it again, too: I kicked out this novel in a few weeks, a zombie novel, The Gospel of Z, and it was huge and sprawling, has these Gravity’s Rainbow layers of characters all clawing around at the edge of the page, just without whatever excellent magic Gravity’s Rainbow had that lets it work. And I could tell, too: the thing was too big to live. But I couldn’t wedge into it any helpful way, to see where to apply the proper narrative leverage. So, what I did this time, just to identify the dramatic line, it was adapt the story across to a screenplay. At which point trumpets sounded, lions roared, other good stuff happened: the story made sense. So, instead of rewriting the novel, I adapted the (adapted) screenplay into a novel form. And now that novel, it kind of sings.

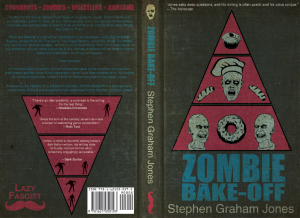

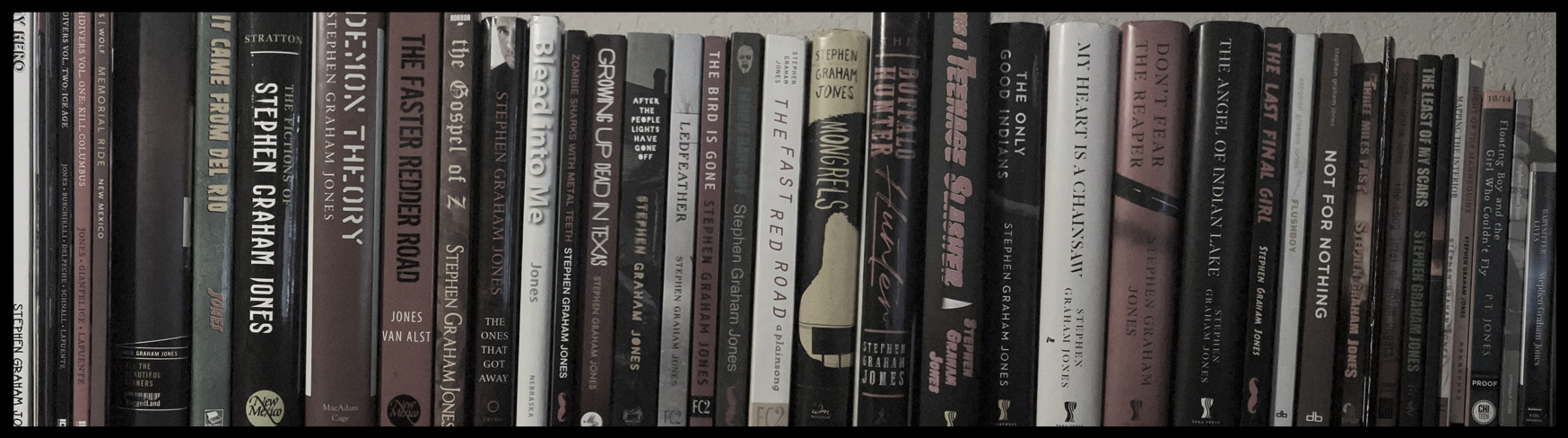

Anyway, without having written Zombie Bake-Off alongside its own screenplay, so that neither would have priority, I never would have known that a trick like that could have a chance. But it had worked with Zombie Bake-Off, anyway. It allowed all the movie-stuff to develop in the screenplay, and all the local-to-prose-fiction fun happen in the novel, and for some cross-pollination to happen with each sentence. I mean, it still feels movie-ish, no doubt, and, since rewriting that screenplay ten-thousand times a year or two ago (with Robert Gatewood, who really knows his stuff), there’s definitely some different developments, some different economies in play, but still, it’s that closed-door, adrenaline rush kind of survival/journey story I had going on in my head. And, sure, in the version in my head there’s David Arquette, there’s The Rock, but that only makes it more real, for me. There’s even some sketches of the main players in ![]() ZBO floating around—I was working with an artist for a comic version. But, by the time I was talking to Cameron Pierce and Lazy Fascist, the novel was the primary mode for the story to live in. And I’m lucky he chose to take a chance on it. And that he pulled Matthew Revert in to do that excellent, excellent cover.

ZBO floating around—I was working with an artist for a comic version. But, by the time I was talking to Cameron Pierce and Lazy Fascist, the novel was the primary mode for the story to live in. And I’m lucky he chose to take a chance on it. And that he pulled Matthew Revert in to do that excellent, excellent cover.

So, what I hope with Zombie Bake-Off, it’s what I hope each time out: that people see that it’s got a beating heart at the center of it. Mine, I guess. Like always.

stephengrahamjones

boulder, co

6 february 2012

Amazing! Those looks into your creative process are always fascinating and weird! But now I want to know what you thought about Egolf’s Kornwolf.

Also, did Rob Zombie draw that last pic himself? It’s insane how many talents he has.