Adolescence and lycanthropy are the chocolate and peanut butter of the horror world. All this strange body hair, an insatiable appetite, late hours, sleeping at all the wrong times, nights you can’t really remember, can only piece together flashes of. A pretty sincere distrust of what are seeming to be your instincts, and everybody looking at you like they know, so that you feel pressured to only hang out with your pack, with who you can trust, those who share your affliction. Uncontrollable drooling. Your body’s asserting itself, reminding you that you’re an animal. So, the same way that we tell ourselves ourselves zombie stories to deal with the looming specter of our own mortality, we’ve been telling ourselves werewolf stories to try to navigate our own various liminal states. Werewolf stories poke and prod at the boundaries of what it means to be human, what it means to change, and, after the crib, where we change the most, that’s high school, isn’t it? It’s where we figure out who we are, who we don’t want to be.

Adolescence and lycanthropy are the chocolate and peanut butter of the horror world. All this strange body hair, an insatiable appetite, late hours, sleeping at all the wrong times, nights you can’t really remember, can only piece together flashes of. A pretty sincere distrust of what are seeming to be your instincts, and everybody looking at you like they know, so that you feel pressured to only hang out with your pack, with who you can trust, those who share your affliction. Uncontrollable drooling. Your body’s asserting itself, reminding you that you’re an animal. So, the same way that we tell ourselves ourselves zombie stories to deal with the looming specter of our own mortality, we’ve been telling ourselves werewolf stories to try to navigate our own various liminal states. Werewolf stories poke and prod at the boundaries of what it means to be human, what it means to change, and, after the crib, where we change the most, that’s high school, isn’t it? It’s where we figure out who we are, who we don’t want to be.

So, yeah, the hook of 1957’s I Was a Teenage Werewolf — a redundant title, yes? — was that this Michael Landon kid’s going all Lon Chaney in the halls, but, unlike The Wolf Man (1941), he’s using lycanthropy to navigate his social space, a dynamic that really came into its own with 1985’s Teen Wolf update, where Michael J. Fox can, with his newfound wolf powers, suddenly slam the basketball, win the game, become the hero he’s never been. Twenty years later, then, Wes Craven and Kevin Williamson gave us Cursed, which had the promise to be the apotheosis of all this adolescence/werewolf fun, but then it ended up too preoccupied with riffing on 1981’s American Werewolf in London. However, five years before Cursed, we’d been delivered Ginger Snaps, which was everything Cursed wasn’t: an intelligent dramatization of what the ‘curse’ might mean for a pair of outcast sisters. And, while Ginger Snaps rode high on the video shelves and is still very alive a decade later, it never was the theatrical success of even, say, Silver Bullet (also 1985 — a scant four years after the seminal Wolfen and The Howling; 1981 was a banner year for werewolves).

However, that’s all big screen. On the television, the first werewolf I remember was on a CHiPs episode, though of course werewolves have been everywhere, from X-Files to Buffy, from True Blood to (of course) Wolf Lake, and likely a lot of pre-seventies stuff I’ve never even heard about. There was even an animated Teen Wolf in the eighties, and I’m sure Scooby’s dealt with a few. However, one thing you notice immediately with (live-action) television lycanthropy, it’s that that money shot we always expect on the big-screen, it’s not in the budget, here: there’s no long, painful, drawn-out transformation sequences like The Wolf Man famously pioneered and Landis made an artform, there are no “I want to give you a piece of my mind”-lines. And it makes sense: for something in serial form, you don’t want to have to spend days of production on what’s finally a repetitive part of your story. So you either get the True Blood transformations, which are fast and easy, practically off-screen, or you get the “muttonchop werewolf” look, where the actor’s suddenly just got fangs and sideburns. Check the werewolf arc on Wizards of Waverly Place, say. Or, Mtv’s current Teen Wolf incarnation.

However, I’m not meaning to sell this Teen Wolf short, either. Only two episodes in, there’s the suggestion that there’s different types of werewolves: the ‘animal’ and the ‘human’ — ones that look like the Dogman of Michigan or The Derrider Roadkill (just with cool back legs), and ones that are more muttonchoppy. Too, though, we’re a sophisticated audience; we all know there’s different types of werewolves, running from the ‘smart wolves’ which are all wolf (this keeps the special effects budget down) to the CGI werewolves of Harry Potter, from the shoulderpadded werewolves of Dog Soldiers and Underworld to the Jack Nicholson variant. And, with Mtv’s Teen Wolf, you kind of suspect that these two types are just gradients of the same creature, just as the blood-starved vampires in Daybreakers are ‘reduced’/primal vampires — they’re Lestat, living off frogs in the swamp for a few months. And, granted, the transformation sequences in Teen Wolf so far are nothing special — cool contacts, claws, sideburns, a bit too much slow-motion to show them all off — but, like I was saying, if we’re going to be seeing this every week, we need some visual code for transformation, not that whole transformation each time. And, as for explaining the actual ‘how’ of growing all this hair in seconds — how many calories must that take? — or dealing with aging-while-canine (as Robert McCammon so excellently does), or watering down the werewolf’s appetite, making it go ‘vegetarian’ as Twilight would have it . . . we’ll see. But they do have fangs, anyway. And, finally, as with all werewolf stories, it’s not really the werewolf’s classification or history that matters. It’s its social milieu.

However, I’m not meaning to sell this Teen Wolf short, either. Only two episodes in, there’s the suggestion that there’s different types of werewolves: the ‘animal’ and the ‘human’ — ones that look like the Dogman of Michigan or The Derrider Roadkill (just with cool back legs), and ones that are more muttonchoppy. Too, though, we’re a sophisticated audience; we all know there’s different types of werewolves, running from the ‘smart wolves’ which are all wolf (this keeps the special effects budget down) to the CGI werewolves of Harry Potter, from the shoulderpadded werewolves of Dog Soldiers and Underworld to the Jack Nicholson variant. And, with Mtv’s Teen Wolf, you kind of suspect that these two types are just gradients of the same creature, just as the blood-starved vampires in Daybreakers are ‘reduced’/primal vampires — they’re Lestat, living off frogs in the swamp for a few months. And, granted, the transformation sequences in Teen Wolf so far are nothing special — cool contacts, claws, sideburns, a bit too much slow-motion to show them all off — but, like I was saying, if we’re going to be seeing this every week, we need some visual code for transformation, not that whole transformation each time. And, as for explaining the actual ‘how’ of growing all this hair in seconds — how many calories must that take? — or dealing with aging-while-canine (as Robert McCammon so excellently does), or watering down the werewolf’s appetite, making it go ‘vegetarian’ as Twilight would have it . . . we’ll see. But they do have fangs, anyway. And, finally, as with all werewolf stories, it’s not really the werewolf’s classification or history that matters. It’s its social milieu.

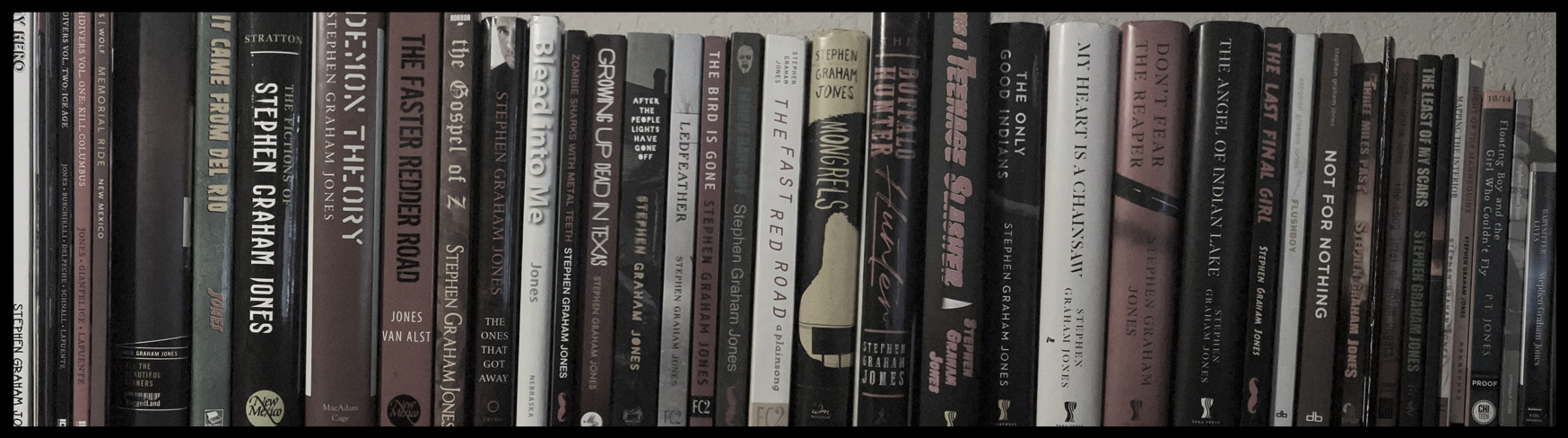

Enter Scott McCall, who we know’s not king of the high school halls because of course he’s got an inhaler and doesn’t start for his the lacrosse team (his high school’s Quidditch). Also enter Allison Argent, the new supermodel at school, whose name evokes not just Lou Diamond Philip’s ‘John Kanin’ from Wolf Lake but Matt Wagner’s main Grendel-foe, ‘Argent.’ But if we can accept Inception’s ‘Ariadne’ webmaster, then swallowing one more werewolf pun should be second nature (‘loup-garou’ has been killed to death as well, and did we ever not know Lupin was a werewolf?). And, yes, as the genre dictates, enter one suspicious creature prowling the moors, as it were, providing the bite-and-run catalyst we need to see how this new infection’s going to play out come Monday morning, when schools starts. Also of interest here, talking about werewolf tropes, is that both McCall and who finally emerges as  maybe the biter, they’ve got dark hair. Just like Taylor Lautner’s Jacob, from Twilight, which itself is already evoking the Indian werewolves of X-Files, CHiPs, etc. I used to always think this was kind of a backhanded kind of compliment, making Indians be the werewolves — kind of typecasting us as ‘that’ close to nature, to our ‘animal selves,’ I don’t know. Or maybe if we’re predatory animals there’s just less guilt about killing us. It feels responsible, even. But I finally don’t think that’s it. I think what’s going on is as simple as hair color: outside of Ginger Snaps — which used it — you don’t see many blond werewolves, do you? Because . . . I don’t know. All our socialized ideas and preconceptions about white and black? Because seeing the ‘darkness’ take shape is scarier than having a frosted-with-highlights creature step out from behind the tree? Because the effects crew finds it easier to work with dark fur? Because ‘swarthy’ equals ‘dangerous’ somehow? Pirates tend to be brunette as well, I guess, don’t they?

maybe the biter, they’ve got dark hair. Just like Taylor Lautner’s Jacob, from Twilight, which itself is already evoking the Indian werewolves of X-Files, CHiPs, etc. I used to always think this was kind of a backhanded kind of compliment, making Indians be the werewolves — kind of typecasting us as ‘that’ close to nature, to our ‘animal selves,’ I don’t know. Or maybe if we’re predatory animals there’s just less guilt about killing us. It feels responsible, even. But I finally don’t think that’s it. I think what’s going on is as simple as hair color: outside of Ginger Snaps — which used it — you don’t see many blond werewolves, do you? Because . . . I don’t know. All our socialized ideas and preconceptions about white and black? Because seeing the ‘darkness’ take shape is scarier than having a frosted-with-highlights creature step out from behind the tree? Because the effects crew finds it easier to work with dark fur? Because ‘swarthy’ equals ‘dangerous’ somehow? Pirates tend to be brunette as well, I guess, don’t they?

Whatever it is, this dark-haired Scott McCall, yep, he gets bitten, luckily has a (blond-ish) friend with internet tendencies who can look up this particular affliction, and of course this new Argent girl’s smoldering her eyes at him, and, as he doesn’t need his inhaler, he can seriously jam at lacrosse now, can get that golden snitch each time. Well, if he can just keep the wolf in check — which is where this Teen Wolf’s harkening back more to the Michael Landon version, not the more antiseptic Michael J. Fox version (in its defense, though, the second Teen Wolf was built for the movie theater, not the drive-in). Aside from there being different body-types with werewolves, there’s also differences in what activates the lycanthropy: for some it’s the moon, for some it can be blood, or menstrual cycles (see Justine Larbalestier’s Liar), for others it’s a willpower thing, for Michael Jackson it was the beat, I guess, and, for McCall, here, it’s the Incredible Hulk version — anger. He can’t turn it on and off like might be convenient, but — at least for now — is victim to his own hormones, his own inner turmoil, which is helping him on the lacrosse field, yes, maybe even giving him some pheromones to get the new girl interested, some ears and a nose that are pretty good expositional tools, but it’s also endangering everybody around him.

Which is to say, yes, he’s a teenager. He’s having to figure out how to control himself, and he’s in a situation — there’s mystery, there’s intrigue, there’s people already after him — that serves simply to dramatize that, to make it interesting. Who wants to read about a kid just growing up, right? We are a sophisticated audience, yes, but we’re also an audience with a low tolerance for boredom. So, dress that growing-up in some tattered clothes, give it some claws and teeth, and Teen Wolf’s off and running, looks to be one of the stronger werewolf outings in a long while, now, and will hopefully give us a few seasons of blood and lessons.

Y’know, though I don’t care much about werewolves in particular, I had to say this was a very well-written and entertaining article to keep me glued throughout in spite of this fact. I also think it’s stupidly-clever that the were-bar on True Blood is called Lou Pine’s. Totally missed that at first.

anybody notice that, in this week’s TEEN WOLF, when we could really see a wolfed-out-all-the-way werewolf running and running hard, that it kept its back legs together like an ambush predator? which is good and fine, except that was an ‘alpha’ wolf, of a pack, and — packs tend to practice persistence hunting, don’t they? they run their prey down, nipping at it on the way. whereas Streiber’s wolfen, of course, they were sleek, ran like a horse, or a coyote. but maybe the CGI animators aren’t talking to the story people, here, so, in my head, at least, I can still believe. though the red eyes: I don’t know. I’m failing to see the advantage that gives, either in hunting or breeding (unless abject terror ‘freezes’ the prey, the mate(s)?). but maybe it’s like the horsemen in Mongolia used to carry mirrors, to signal across the distances. except wolves have all this pheremone and scent stuff going on . . . I don’t know. but I’m still watching it, and loving it.

“Blood and Chocolate” They’re slightly older than teenagers and you get your blonde wolf. I liked it.

( math?)

this season of teen wolf will be kick a** http://www.teenwolf5.com