This originally ran on Spinetingler back in 2012, when Growing Up Dead in Texas was new. Now Spinetingler’s gone gone gone, though, and somebody got hold of me, asked where was this, and . . . I’m not so sure, really. But I did dig this up from an email. It’s some version of what went up at Spinetingler lo those many years ago. From a. URL I found for it, the first part of the title, evidently, was “That Pink Light at the End of the Tunnel,” but then some URL clipper, you know, clipped it, so I don’t know how it ended. Something with PKD maybe? Hopefully?

Anyway, here’s the paste-in:

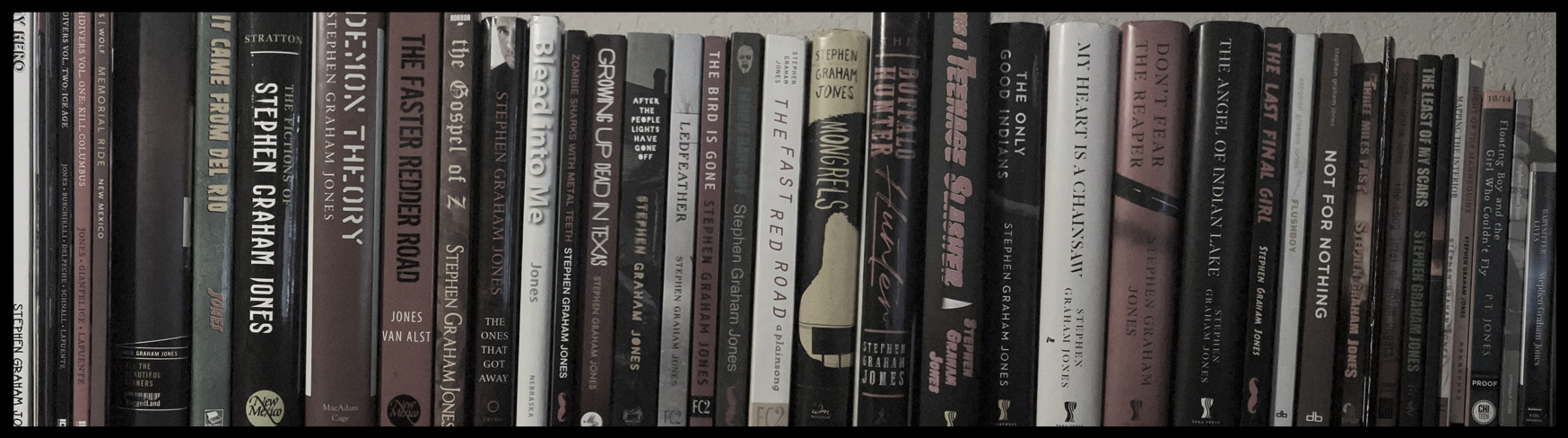

Growing Up Dead in Texas took me some thirteen weeks to write. My first novel took me ten months—my record. The fastest I’ve ever done it’s three days, and I guess I’ve done that twice now, though only one of them deserved to be published. I average about six weeks a book, probably. I mean, once I start writingthe book, once I luck onto the voice that activates the premise, once the characters start talking in my head, once I start dreaming the story, all that, then, yeah, six weeks is pretty close. Ledfeathertook four months, I think, but that was zero to sixty: the publisher called, said, hey, what about a novel? I jammed through the end of the novel I was already writing and, four months later, turned Ledfeatherin. I’m writing a novel right now that’s going to tap out at about three months, I think. I jammed down a hundred pages over a couple of weeks in March, then let myself get tied up with other writing obligations—kicked out thirty or forty thousand words of solicited stories—but am hunched over the keyboard again, have gone sixty or eighty pages the last four or five days, and just today accidentally figured out the five steps that are going to get me to the end.

And, yeah, I say Growing Up Dead in Texastook thirteen weeks to write, but, give it a try, you’ll see it’s one of those books that, in my case, probably took thirty-six years to write, really. First I had to live through it all, then let it percolate, then give myself permission to pretend I’m making it all up—that old story. People say that, because we’ve all lived through childhood, all of us are stocked with all we need for a lifetime of writing. They’re not wrong, I don’t think. But still, when people ask—and this is always a question—my answer for this book: Thirteen weeks or so. But then I have my own question, that I never ask back: Why?

For some reason fiction is saddled with the myth that the amount of time invested in a book or story, it’s a thumbnail guide for how much time the readershould invest. Or, maybe it’s not how much ‘time’ the reader should invest, but how ‘deeply’ or ‘earnestly’ they should read—whatever the currency, the presupposition is that Great Art is something the artist had to strain over for years, that Great Art becomes ‘great’ specifically because the artist had to sacrifice a decade to it. That it’s all that effort that finally makes the art worthwhile.

I submit that this is faulty reasoning.

No, let me rephrase: I submit that this is completely stupid.

I mean, the easy and obvious objection is that we’ve all read terrible works that took years to complete, works that have been mulled over so compulsively that all that’s left is mush. But we’ve also read ten-year books that are untouchable, that are perfect, that are the pinnacle of what can be done with squiggly marks on a page. And of course the coin flips the other way as well: plenty of fast books feel like fast books, like something dashed off in a few days. But some of them don’t. Some of them are alsoperfect, are alsothe pinnacle of what can be done on the page. I don’t want to start listing titles. here—you’ve got your own, anyway—but . . . can you imagine a market where you pluck a book off the shelf, flip it over to the back cover, and there’s a little industry-standard timestamp? This work of fiction took three years four months and five days to complete.Then you could bite your lip in a bit, look around, and slip this into your cart, pretty well assured that you’re about to unpack all the time the writer’s already packed in.

I submit that this is already the market.

Look at the publicity of so many of the books, at all the writers and publishers trying to stake their work out as ‘important’ solely because it was a ‘five-year project.’ It’s the weakest, most base marketing, is so much more insulting than a writer selling copies by pretending he or she lived through this or that. Those writers, they’re at least playing fair. If we take their ‘non’-fiction at face value, if we accept it uncritically, then we’re getting what we deserve: fiction. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But, if the marketing engines are trying to convince us that ‘five years’ is a worthy or even reasonable amount of time for a work like this, then what they’re doing is taking any judgement of the work out of our hands. They’re saying we’re not smart enough to decide if the story’s quality or not. And, sure, this is the nature of the marketing machine: if it can maybe get away with faking a ‘certified’ stamp, then it’s pretty much compelled to try. Whatever moves product, all that.[*]I can live with that; we all know marketing is fairly soul-less.

The problem, though, is that that prejudice against novels that take a week or a month or anything under three years to write, we internalize it. To the degree where you can almost hear an ‘only’ between my thatand takein that last sentence, yes?

It’s infected us all. Even me. Last summer I kicked a novel out in thirteen days, and, at the end of it, I found myself kind of looking askance at that book, like maybe I should digest it some more, like maybe I should peel through with a more critical knife. But then I read it again, and again, and, man, it was doing precisely what it was supposed to do. Which doesn’t at all mean it’s no-doubt good—essentialism in either direction needs to be swatted—but I’m seriously worried that too many writers are out there taking those five-year-novelists as their model, and, as a result, overwriting (see: killing) what might have been some of the most beautiful, accidental works.

And please understand that I’m not arguing for the hare over the tortoise. There’s another side to this, I mean. If you’re one of those writers who are built such that it takes you ten years to kick a novel out, then, man, I can’t even begin to imagine that kind of pressure. You have no room to fail, do you? No room to learn. Because, all your friends, your family, your teachers, they know what you’ve been doing all this time, and, now, finally—cue some trumpets—you’re handing over your holy manuscript that’s going to change the world.

Only, maybe it’s just normal. Or not even that.

I’m not talking about no return on your investment of time, I’m talking about how, if you’d written it in ten days instead of ten years, then our current set of prejudices would shrug, say, Oh well, write another. You’re learning, here. This is how it goes.

No, if you’re a ten-year-novelist, then you’ve got no choice: if you don’t turn in something that absolutely sings, then you’re a failure. And that, I think, probably kills just as many beautiful novels (andnovelists) as those guilty writers who don’t trust their two-week accidents, so make themselves go back in again and again, turn the story to mush.

People write at different paces. Stories happen in their own time. There’s no right measure of time to get it on the page and there’s no wrong measure of time. There’s simply stories that work and stories that don’t work, and when they work, it’s due to the talent and craft and luck and grit of the writer, never to how many days this story X’d out on the calendar.

We’ve all heard that old story about Picasso paying his bill with a quick little drawing on a napkin, right? How the owner or whoever said, But this doodle only took you fifteen seconds. Picasso’s comeback: Yeah, but it took my fifty years to learn to do it in fifteen seconds.

We should all doodle so well.

[*]Verymuch related: aren’t novels often judged by how long it takes us to peel through them? There’s ‘beach reads’ that fly by and there’s epic family sagas chiseled in prose that you trade a month of your life for, and we give more literary weight to the sagas, just because we want our time to have been worth something, to not have been spent frivolously (as if there’s anything wrong with simple entertainment). But we’re setting ourselves up, there: padding a story out, either with density or page-count (or, sigh: both), that’s the easiest trick there is, and is no more a guarantee of quality than ‘defending’ a book with how long it took to write.